Autumn is migration season in California. We all know that, in the northern hemisphere, birds fly south for the winter and return north for the summer. And indeed, this is a very good time to go bird watching along the Pacific Flyway, as migrating birds stop to rest and feed at places such as Elkhorn Slough. Here in Santa Cruz, autumn is punctuated by the return of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), roosting in eucalyptus trees at Natural Bridges State Beach and Lighthouse Field.

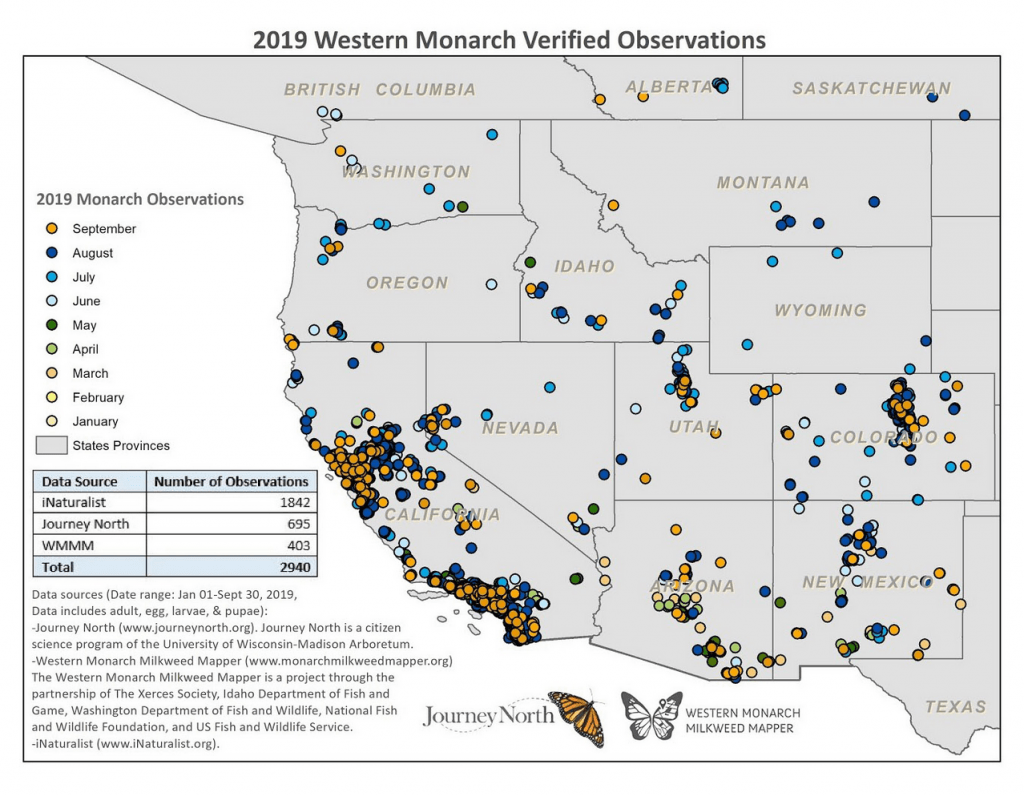

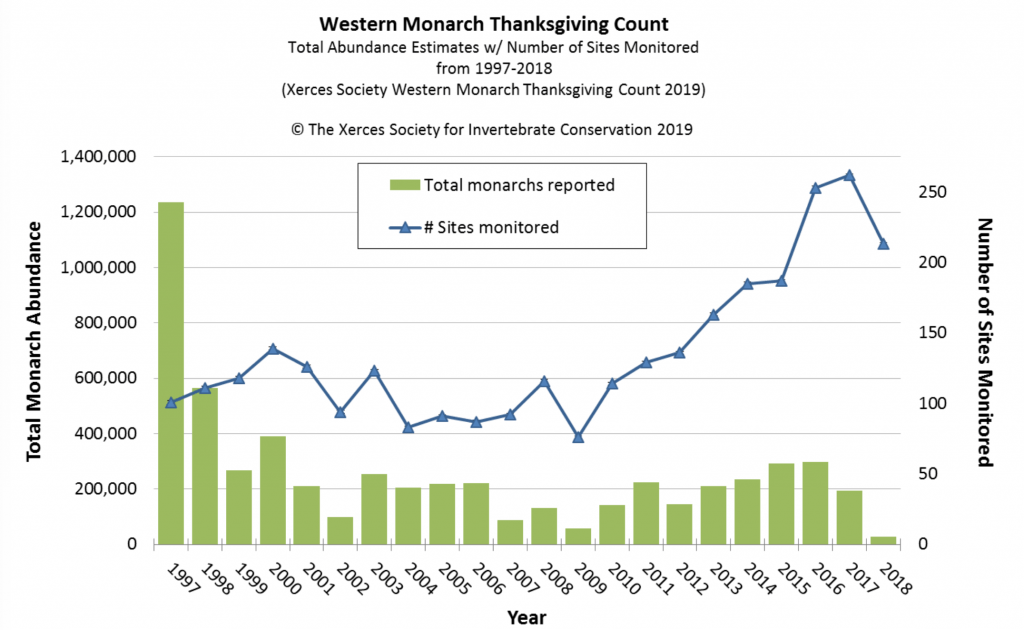

Since 1997 the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation has been tracking monarch sightings on their migrations between the western U.S. and Mexico. They conduct a volunteer butterfly count every Thanksgiving. More recently, community science data sources such as iNaturalist provide much of the information.

This morning, before it got warm, I went to Natural Bridges to see how the monarchs were doing. I wanted to photograph clumps of butterflies dripping from tree branches. It seemed, however, that there aren’t as many butterflies as I remember from previous years. The clusters were not nearly as large or as dense as they should be. And the data shown in the figure below do demonstrate a precipitous decline in monarch since 2017. We’re still a couple of weeks away from this year’s Thanksgiving count, and there is still a chance that the butterflies might arrive in larger numbers.

Trained observers know how to estimate the number of butterflies in a cluster like this. The numbers of butterflies at various roosting sites are aggregated to assess overall population sizes.

11 November 2019

© Allison J. Gong

This morning I did see one butterfly that had a tagged wing. It was wearing a green Avery round sticker, with some writing in what looks like black Sharpie. The color of the sticker was very close to the green of the surrounding foliage, so I wasn’t even able to see the sticker until I downloaded the pictures from the camera.

11 November 2019

© Allison J. Gong

At first I thought the tag resulted from an official scientific project or undertaking, but it turns out that anyone can tag a monarch. The tags are used to track migration of the butterflies. There doesn’t seem to be a central depository of tags and their origins, so knowing the color of the tag doesn’t tell me where this particular butterfly came from.

Once the sun hits the butterflies and they begin to warm up, the clusters start breaking apart. Butterflies open and close their wings, exposing the darker dorsal surfaces to the sun and warming up their flight muscles. Sometimes they dislodge one another.

On a cool morning like this, many of the butterflies that fell out of the clump couldn’t fly yet, and landed on the ground. The boardwalk is perhaps not the safest place for a butterfly to wind up, but at least in a monarch sanctuary such as Natural Bridges the visitors are knowledgeable and look out for the butterflies’ safety.

11 November 2019

© Allison J. Gong

As I wrote before, the butterflies we see at Natural Bridges this year were not born here. This means that their survival to this point has depended on healthy conditions in the Pacific Northwest and the western slopes of the Rocky Mountains, where they lived as caterpillars and emerged from their chrysalises. This also means that planting milkweed for monarch caterpillars in California won’t help the butterflies that we see here, although it would help butterflies that are destined to overwinter elsewhere. What will help local butterflies–monarchs and otherwise, and all nectar-feeding insects, in fact–is planting California native plants, to provide them with the nutrition they have evolved to survive on.