My most recent batch of sea urchin larvae continues to do well, having gotten through the dreaded Day 24. I haven’t written about them lately because they’re not doing very differently from the group that I followed last winter/spring. However, I’ve been taking photos of the larvae twice a week and it seems a shame to let them go to waste, so I’ve put together a progression of larval development. As a reminder, the last time I wrote about these larvae they were six days old.

Age 9 days: The larvae had four arms and were growing their skeletal arm rods. Their stomachs, which we keep an eye on because their size can tell us whether or not we’re feeding them enough, were a bit small but not so much so that I worried.

13 November 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Age 12 days: The larvae were growing their third pair of arms. Some had just begun growing the fourth pair of arms. Red pigment spots also start appearing all over the body. Some larvae develop lots of red spots, others have very few. Notice that the stomach is slightly pear-shaped; this is normal.

16 November 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Age 17 days: This larva doesn’t look appreciably different from the previous one. This photograph, though, is a bit clearer. The stomach has taken on a pink tinge, due to the red color of the food the animal is eating, and the mouth is the large rounded triangular in the in-focus plane. The pair of skeletal arm rods that are in focus are protruding from the ends of the arms, which raises is something to be concerned about. Sometimes the first sign of imminent doom is the shriveling of the arms, so seeing the rods sticking out makes me think “Uh-oh. . .”

21 November 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Age 24 days: This is about the time in larval development when things often start to go wonky. I’ve looked back at my notes from previous spawnings of S. purpuratus, and seven of the 20 cultures that crashed did so in the week between days 20-28 of development. Some of these cultures were doing well right up to the point that they all died. They were literally there one day and gone the next.

Nonetheless, the current batch of larvae continued to do well. The fourth pair of arms were slow to grow but otherwise the larvae look fine. The top larva in the picture below is lying on its back, so you are looking onto the ventral surface. On the left side of the stomach there’s a little upward-facing invagination; this is part of the initial water vascular system forming. Note also that the overall shape of the larvae is changing a bit. They are becoming less pointy and a bit rounder.

28 November 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Age 30 days: At this stage the juvenile rudiment is clearly visible. You can see it as a rather nondescript blob of stuff to the left of the gut. The fourth pair of arms have also grown quite a bit but are still considerably shorter than the others. This individual has two bands of cilia, called epaulettes, that encircle the body. These epaulettes will become more conspicuous as the larva approaches competency.

4 December 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Age 33 days: Today I got lucky! The larvae looked good when I changed their water this morning <knock on wood> and although I’m keeping my fingers crossed I have high hopes for these guys. They’re about as big as they’re going to get, measuring 760-800 µm in length. They will get heavier and more opaque as the juvenile rudiment continues to develop.

7 December 2015

© Allison J. Gong

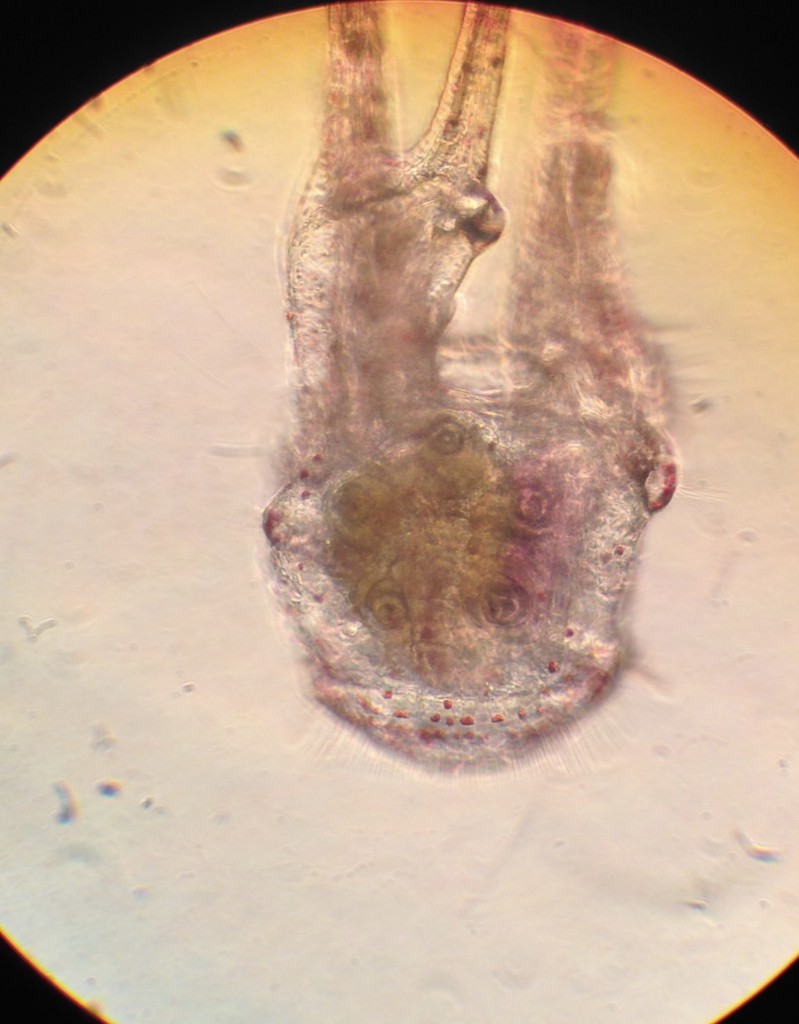

The really cool thing is that one of the larvae landed on the slide exactly as I wanted it to. It happened to fall onto its left side and stayed there, so I was able to focus up and down through the body to get the rudiment into focus.

7 December 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Do you see five small roundish blobs that are evenly spaced around the larger golden circular blob? The large blob is the stomach, seen in side view. Those smaller blobs are tube feet! Don’t believe me? Then take a look at this close-up:

7 December 2015

© Allison J. Gong

Now if those don’t look like tube feet, then I’ll eat my hat. What’s also noteworthy about this larva is that its epaulette bands are both visible, especially the posterior-most one.

So far, so good. I won’t know how successful larval development is for these guys until they either make it through metamorphosis, or not. In a very real sense, I won’t be able to draw any conclusions about the success of larval development until they either become established as juvenile urchins, or not. One of my graduate advisors inherited a couple of sayings that he passed on to me, as well as to a whole generation of aspiring invertebrate zoologists:

The animal is always right.

and

The life cycle is the organism.

The first is a given, right? The animal knows what it is and what it’s doing, even if we humans have no clue about what’s going on and can’t decide what its name should be.

The second saying might be a little less intuitive. What it means is that, for organisms with a multi-stage life cycle, you have to consider all of the stages if you want to understand them. This is a much more holistic view of biology, and it’s the one that appeals most strongly to me. When I’m thinking as a naturalist, I find my thought process constantly switching between “forest” and “trees” as I seek to understand even a teensy bit of the world around me. While it’s easy to get distracted by all the cool details of organisms, it’s important to step back and ask myself, “What does it all mean? What is the big picture here?” So yeah. Perhaps when (if!) these larvae turn into urchins and I’ve got them feeding on macroalgae in a few months, I’ll be able to say whether or not larval development was successful. If all goes well this larval phase, as all-consuming and fascinating as it is to me, will be only a small part of these animals’ lives.