The intertidal sculpins are delightful little fish with lots of personality. They’re really fun to watch, if you have the patience to sit still for a while and let them do their thing. A sculpin’s best defense is to not be seen, so their first instinct is to freeze where they are. Then, if a perceived threat proves to be truly frightening, they’ll scoot off into hiding. They can also change the color of their skin, either to enhance camouflage or communicate with each other.

Around here we have a handful of sculpin species flitting around in our tidepools. Sculpins can be tricky to identify even if you have the fish in hand–many of the meristics (things you count, such as hard spines and soft rays in the dorsal fin, or the number of scales in the lateral line) used to distinguish species actually overlap quite a lot between species. The fishes’ ability to change color means that skin coloration isn’t a very reliable trait. When I was in grad school there was another student in my department who was studying the intertidal sculpins, and she told me that most of the ones we see commonly are either woolly sculpins (Clinocottus analis) or fluffy sculpins (Oligocottus snyderi). I’ve developed a sort of gut feeling for the gestalt of these species, but I’m not always 100% certain of my identifications.

2019-07-04

© Allison J. Gong

Anyway, back to the camouflaged sculpins. The ability to change the color of the skin means that sculpins can match their backgrounds, which comes in very handy when there isn’t anything to hide behind. Since the environment is rarely uniformly colored, sculpins tend to have mottled skin. Some can be banded, looking like Oreo cookies. The fish in this photo lives in a pool with a granite bottom. The rock contains large quartz crystals and is colonized by tufty bits of mostly red algae. There is enough wave surge for these fist-sized rocks to get tumbled about, which prevents larger macroalgae from colonizing them.

Other shallow pools higher up in the intertidal at Asilomar have a different type of rocky bottom. The rocks lining the bottom of these pools are whitish pebbles that are small enough to be tossed up higher onto the beach. I don’t know whether or not these pebbles have the same mineral content as the larger rocks lower in the intertidal, but they do have quartz crystals. The pebbles are white. So, as you may have guessed, are the sculpins!

2019-07-04

© Allison J. Gong

Other intertidal locations have different color schemes. On the reef to the south of Davenport Landing Beach, you will see a lot of coralline algae. Some pools are overwhelmingly pink because of these algae. Bossiella sp. is a common coralline alga at this location.

What color do you think the sculpins are in these pools?

Give yourself a congratulatory pat on the back if you said “pink”!

2017-06-27

© Allison J. Gong

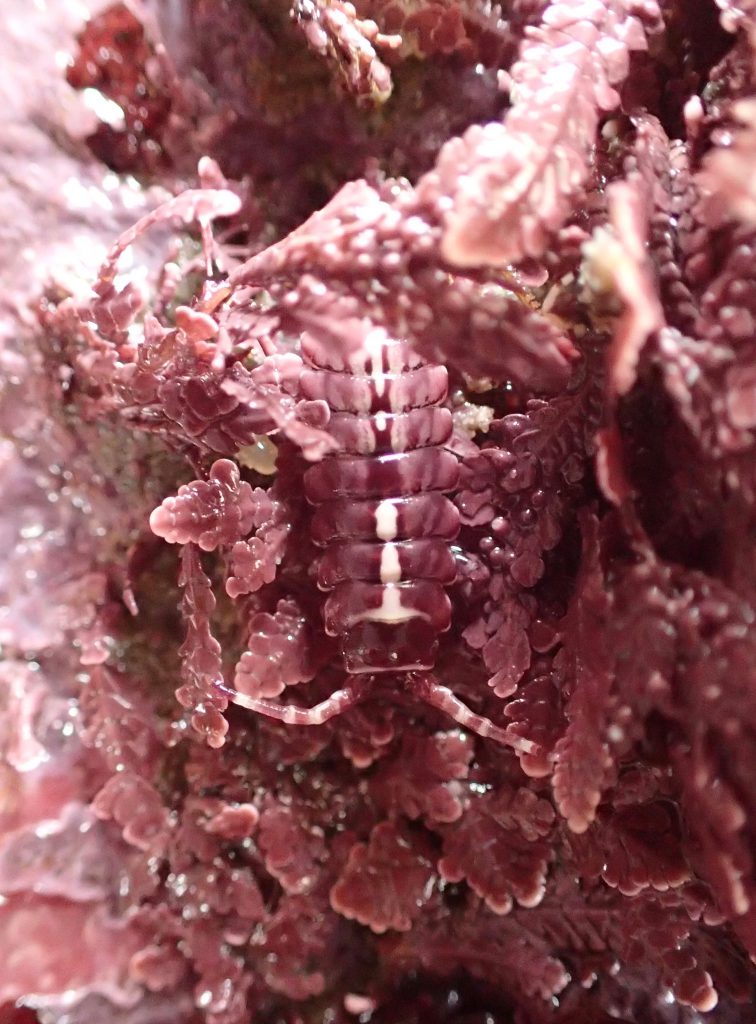

Sculpins aren’t the only animals to blend in with coralline algae. Some crustaceans are remarkably adept at hiding in plain sight by merging into the background. Unlike the various decorator crabs, which tuck bits and pieces of the environment onto their exoskeletons, isopods hide by matching color.

Turning over algae and finding hidden creatures like these is always fun. For example, I saw these isopods at Pescadero this past summer. See how beautifully camouflaged they are?

2017-07-05

©Allison J. Gong

2017-07-05

© Allison J. Gong

Sometimes, when you’re not looking for anything in particular, you end up finding something really cool. Last weekend I met up with students in the Cabrillo College Natural History Club for a tidepool excursion up at Pigeon Point. We were south of the point at Whaler’s Cove, where a staircase makes for comparatively easy access to the intertidal.

2019-11-24

©Allison J. Gong

It’s fun taking students to the intertidal because I enjoy helping them develop search images for things they’ve never seen before. There really is so much to see, and most of it goes unnoticed by the casual visitor. Often we are reminded to “reach for the stars,” when it is equally important to examine what’s going on at the level of your feet. That’s the only way you can see things like this chiton:

2019-11-24

© Allison J. Gong

Mopalia muscosa is one of my favorite chitons. It is pretty common up and down the California coast. However, like most chitons it is not very conspicuous–it tends to be encrusted with algae! This individual is exuberantly covered with coralline and other red algae and has itself become a (slowly) walking bit of intertidal habitat. It is not unusual to see small snails, crustaceans, and worms living among the foliage carried around by a chiton. Other species can carry around some algae, but M. muscosa seems to be the most highly decorated chiton around here. I showed this one to some of the students, who then proceeded to find several others. A search image is a great thing to carry around!

Compared to the rocky intertidal, a sandy habitat can be a difficult place to live. Sand is inherently unstable, getting sloshed to and fro with the tides. Because of this instability there is nothing for holdfasts to grab, so there are many fewer algae for animals to eat and hide in. Most of the life at a sandy beach occurs below the surface of the sand, and is thus invisible to anyone who doesn’t want to dig. There’s a beach at Whaler’s Cove where I’ve found burrowing olive snails (Olivella biplicata) plowing along just below the surface. I wanted to show them to the students, so I waded in and rooted around. I did find Olivella, but I also found a burrowing shrimp. I think it’s a species of Crangon.

2019-11-24

©Allison J. Gong

Now that is some damn fine camouflage! If the shrimp didn’t cast its own shadow, it would be invisible. Even so, it was clearly uneasy sitting on the surface like that. I had only a few seconds to shove the camera in the water and snap a quick photo before the shrimp wriggled its way beneath the sand again.

As I’ve said before, observation takes practice and patience. To look at something doesn’t mean you truly see it. That’s why it is so important to slow down and let your attention progress at the pace of the phenomenon you’re observing. If the only things that catch your eye are the ones that flit about, then I can guarantee you will never find a chiton in the intertidal. And wouldn’t that be a sad thing?