Sometimes even a well-known site can present a surprise. Here’s an example. Yesterday I went up to Davenport to scope things out and see how the algae were doing. This is the time of year that they start growing back after the winter senescence. I also took my nature journal along, hoping to find a spot to sit and draw for a while.

The first thing I noticed was the amount of sand on the beach. Strong winter storms usually carve sand off the beaches, making them steeper. And during the calmer months of summer the beaches are flatter and less steep. Yesterday the beach was very thick and flat. It makes trudging across the sand in hip boots much easier!

The accumulation of sand meant that I could walk around the first point. Unless the tide is extremely low, such as we see around the solstices, the water is too deep for that. But yesterday I walked around it, and it wasn’t until I got to the other side that it occurred to me that: (1) hey, I walked around the point; and (2) I could do that only because there was so much sand. See, a thick beach with a lot of sand makes a mediocre low tide feel lower because the water isn’t as deep as it would be if the beach were thinner. When the tide isn’t low enough for me to walk around the point, I have to clamber down a cliff. The cliff height varies depending on how much sand has built up, obviously, but is about head height for me. Getting down usually involves scooting on my butt and hoping my feet land on something that isn’t slippery. As with most climbing, up is easier and less scary than down.

It’s hard to imagine the amount of sand there was yesterday. Look at this picture.

2021-02-08

© Allison J. Gong

See how the rocks in the foreground end? Usually that’s the edge of the cliff. Yesterday I could have just taken a tiny step off the top of the cliff onto sand. That’s over 1.5 meters of sand in that one spot! If the couple in the background were visiting this area for the first time, they’d have no idea of the conditions that made it so easy for them to get out onto the reef.

There was a lot of sand in the channels between rocks, too.

2021-02-08

© Allison J. Gong

Normally those channels are deeper. You can see that some anemones were able to reach to the surface of the sand, but many more are buried, along with any other critters and algae unfortunate enough to be attached to the lower vertical surfaces. And while some of them will either suffocate or be scoured off as the sand washes away, many will survive and be ready to get on with life.

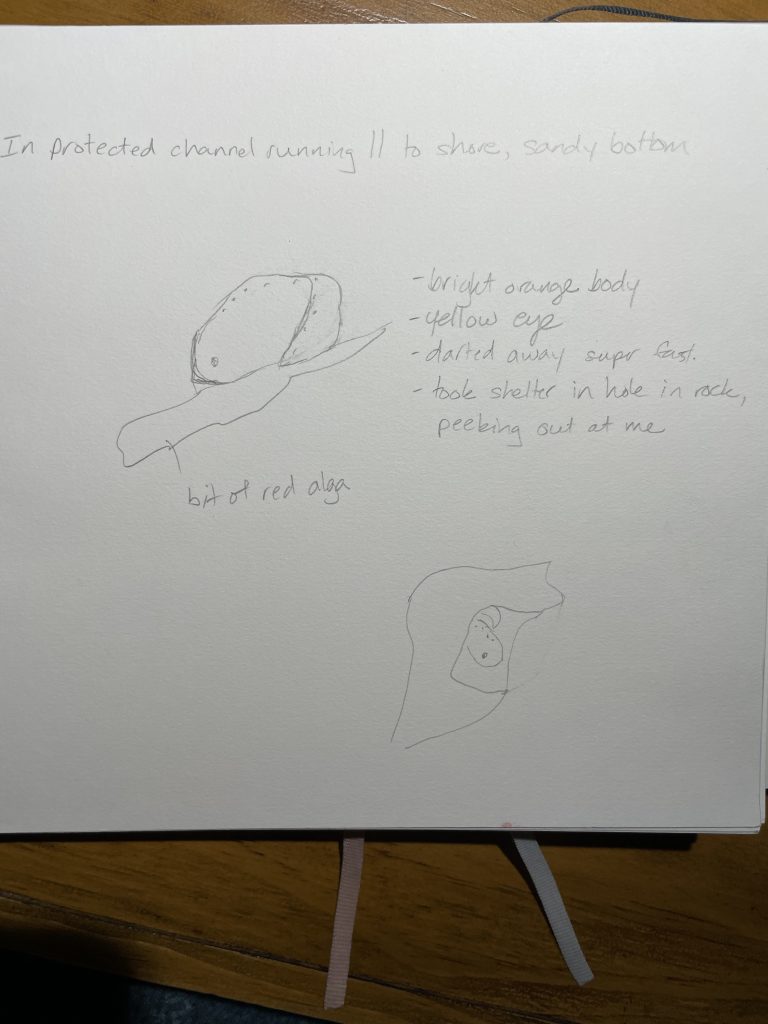

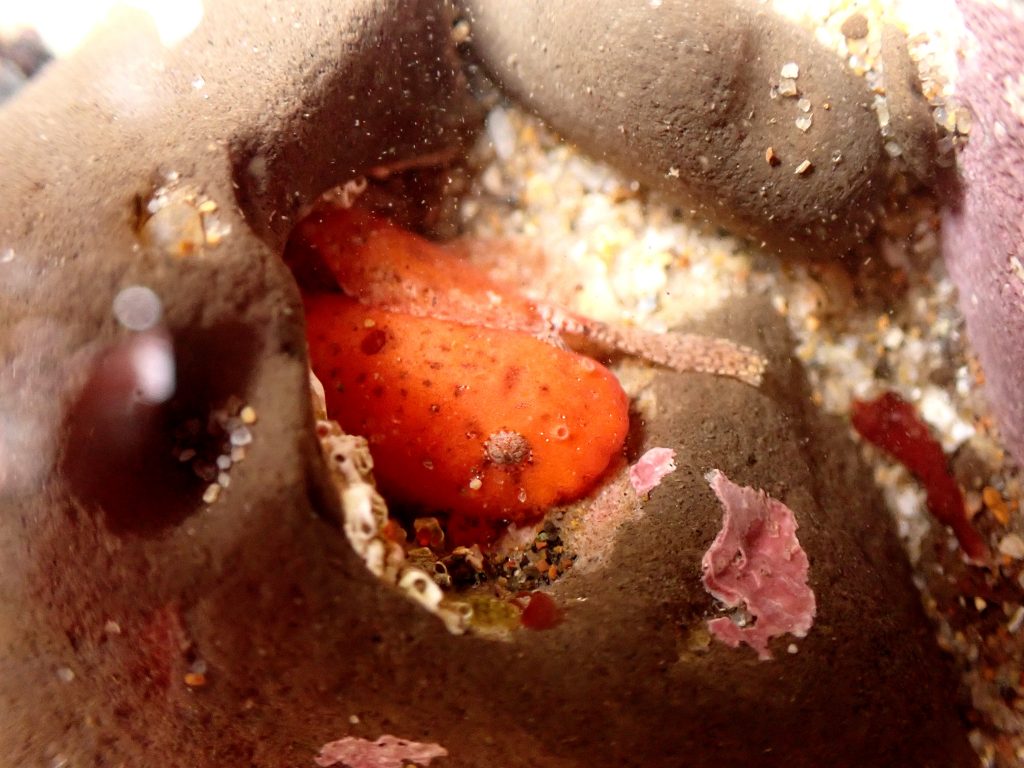

The second surprise of the day was a bright orange object. What I could see of it was about as big as my thumb, and at first I thought it was a nudibranch. Then when I crept closer for a better look, what popped into my head was “snailfish”. Which was an odd thing, because I’d never seen a snailfish before. But something about the creature’s posture looked somehow familiar.

2021-02-08

© Allison J. Gong

Fortunately I had the presence of mind to take photos before trying to draw this little fish, because this is all I had time to get:

When I spooked the critter it took off really fast, confirming that it was no nudibranch. It was, indeed, a snailfish! It came to rest in a small hole in a rock, from where it looked out at me.

2021-02-08

© Allison J. Gong

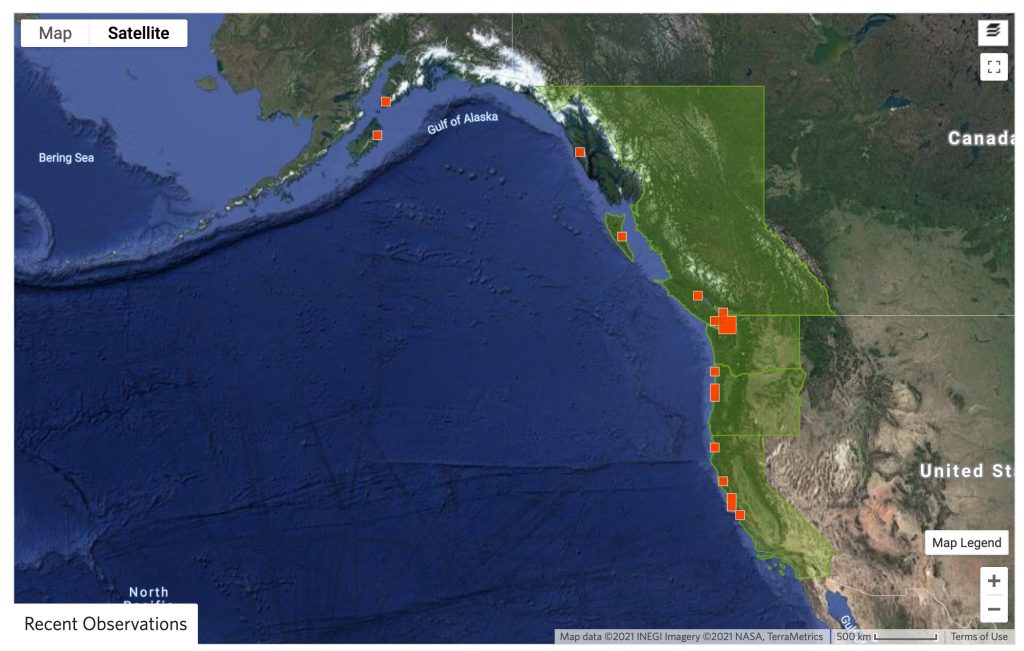

The snailfishes are a very poorly studied group. As a group they are related to the sculpins. There are snailfishes throughout the northern temperate and polar regions, from the intertidal to the deep sea. iNaturalist shows 43 observations of L. florae, eight of which are in California. Before yesterday, none had been recorded at Davenport Landing.

2021-02-09

© iNaturalist

So there you have it, a snailfish! We don’t know much about any of the snailfish species, even the intertidal ones. They apparently have pelvic fins modified to from a sucker, similar to the clingfishes, but I didn’t have a chance to examine this specimen closely enough to confirm that. I don’t know why they are called snailfishes, either. They’re not snail-shaped at all.

Now, about that thing up there where I said “snailfish” came to mind even though I’d never seen one before. That happens quite a bit—a name will jump into my head before I’ve had a chance to think about it. Sometimes I’m wrong, but often I’m right. I know I hadn’t seen a live snailfish before, but obviously I’d seen photos of them or I wouldn’t have been able to recognize this orange creature as being one. It’s fascinating how the brain forms search images, isn’t it?