This weekend a subset of my students and I spent a day at the Fort Ord Natural Reserve (FONR) to participate in the 2018 spring Bioblitz. We were supposed to visit FONR for a class field trip in early March to do some vegetation studies, but that trip was rained out. Today’s visit was sort of a make-up for that missed lab; because it’s a Saturday I couldn’t compel the students to attend, but I offered a little extra-credit for those who did. It just so happened that Joe Miller, the field manager at FONR, had organized a Bioblitz for another group of students, and he welcomed my Ecology class as well.

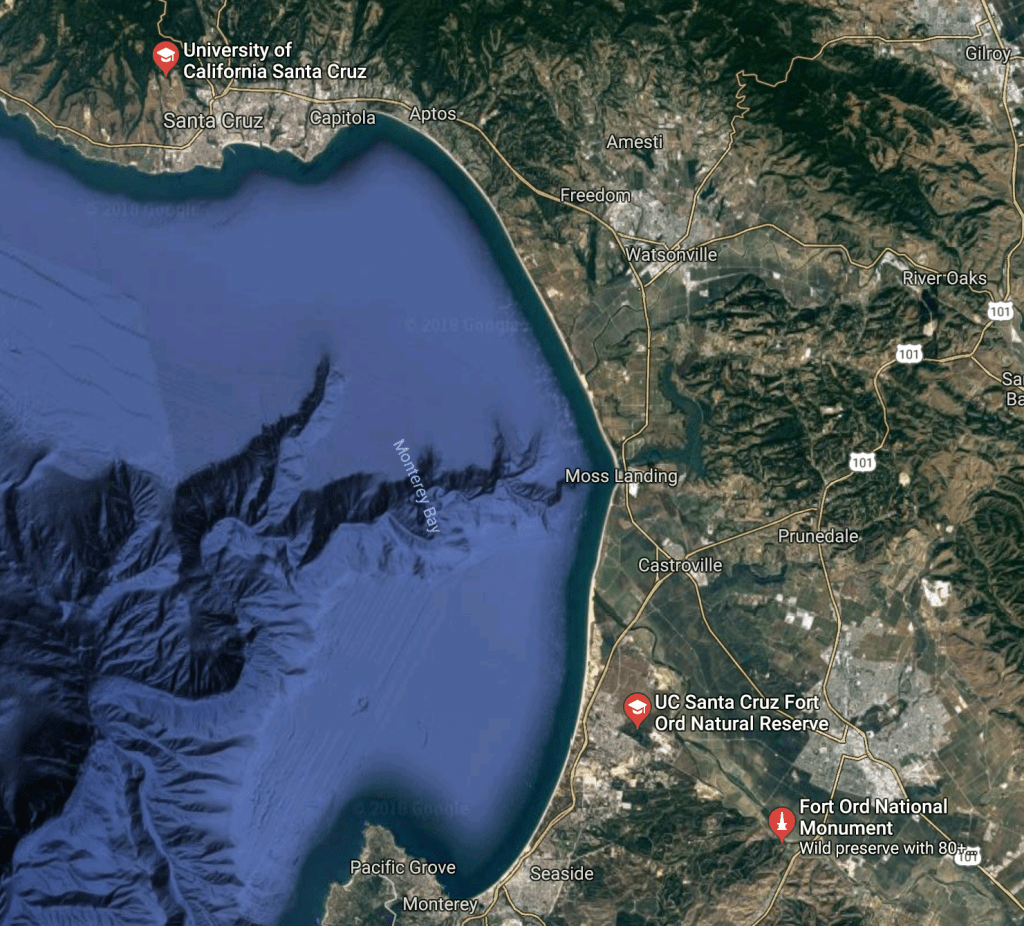

Located adjacent to the city of Marina in Monterey County, FONR is one of five natural reserves administered by the campus of UC Santa Cruz. The other four are the Campus Reserve (on the main campus of UCSC), Younger Lagoon Reserve (on UCSC’s Coastal Science Campus), Año Nuevo Natural Reserve (up the coast in San Mateo County), and Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve (along the Big Sur coast). FONR occupies some 600 acres of a former military base that was closed in 1994. The reserve opened in 1996. As with all the other UC natural reserves, FONR exists to provide students, teachers, and researchers with natural lands to be used as outdoor classrooms and laboratories. Field courses at UC Santa Cruz and CSU Monterey Bay make extensive use of FONR, and students carry out independent studies and internships there.

After all of the participants arrived at the Reserve, Joe described the activities he had planned for the day. He told us that we could wander around the Reserve on our own if we wanted, but there were several hikes we could choose to join:

- One to where some people were finishing up the day’s bird banding activities

- One to collect samples of environmental DNA

- One to ID various tracks in the sand

- One to the different habitats and vegetation types

- One to check out some pitfall traps for small rodents and reptiles

Because my knowledge of the local flora is sorely lacking, I went on the plant hike with Joe. Many of the spring wildflowers had either finished or were finishing up their yearly bloom. The poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum) is looking amazing this year; I think it has been able to take advantage of two consecutive wet seasons with a decent amount of rain. There were many poison oak plantlets scattered around all over the place, and the established bushes are lush and green. There is no way I didn’t come into contact with the stuff at least once on this hike, so today is going to be the true test of whether or not I am allergic to it.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

Much of the terrain at FONR is a maritime chaparral. The soil is extremely sandy (Pleistocene sand dunes, Joe says) with a poor nutrient load and water content. It’s not a desert, because we do get a fair amount of precipitation along the Monterey Bay, but the plants have adapted to thrive with low soil moisture levels. It’s also often very windy, and there are no trees. Even the coast live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), which can be magnificently massive and meandering, are stunted here. Much of the foliage is low-growing perennial shrubs or annual plants.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

Joe led us through the habitats of the Reserve, mostly on trails but also along narrow-to-nonexistent tracks that we called Poison Oak Lane, Rattlesnake Drive, and Tick Alley. And yes, we did see a rattlesnake! My husband spotted it, right about where he was going to put his foot. It wasn’t a big snake, maybe half a meter long, and was sunning itself in a narrow opening between manzanita bushes. I didn’t stop to take a picture because there wasn’t a good space to do so, and I wanted to let other hikers pass the snake quickly. The snake didn’t seem to react to us, but it’s always a good idea to leave them alone.

Just beyond where we saw the rattler, Joe had found a pair of southern alligator lizards (Elgaria multicarinata) mating. When Joe picked them up the male had grabbed the female with a bite behind her head; he does this to keep her from running away, and it also shows his strength and suitability as a father for the female’s offspring. The lizards didn’t like being interrupted in copulo, so to speak, and the male released the female and escaped back to the ground, leaving his lady love behind in Joe’s hand. Hopefully they were able to find each other again once they were both let go.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

To me, the picture above exemplifies what a Bioblitz is all about. We have two people examining a natural phenomenon, and one of them is taking a picture that he will presumably upload to iNaturalist. People learn a lot when they participate in a Bioblitz–they usually see things they’ve never paid attention to before, and when their observations are ID’d or corroborated by the community of iNat experts, they get to put a name to the thing they saw. True, it’s a better learning experience to sit down with a specimen, hand lens, and book to figure out what an organism is, but most people don’t have either the inclination or the luxury of time and the necessary books. And while I’d rather have people look at the real thing with their eyes instead of their phones, getting people to go outdoors and pay any attention at all to their surroundings is a minor victory. I find Bioblitzes to be a little unsettling sometimes. My preferred method for observation is to examine fewer things in greater depth; this is what my graduate advisor Todd Newberry referred to as “varsity” observations. I don’t think a Bioblitz has any place in varsity studies, because of its very raison d’être–to record as many observations as possible–means to some degree that instead of taking a deep look you have to glance-and-go. Still, it does have its place in natural history, and I value it as a way to get more people involved in science.

I was on the plant hike, so many of the organisms I photographed and uploaded to iNat are new to me. Some are California endemics and all have adapted to survive in the difficult conditions of a maritime chaparral.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

And I did see one of the California native thistles. Invasive thistles are such a problem that the knee-jerk response is to stomp on them or yank them out of the ground. This one, for which I’m still waiting on an ID confirmation, is silvery and sort of looks like cobwebs. Joe said that its blossom is a bright pink.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

And one of my newish old favorite wildflowers, Castilleja exserta, was there. The purple owl’s clover occurs throughout California; in 2017 I saw a lot of it on my wildflower excursion to the southern part of the state. It varies in color from purple to pink to white and thus has multiple common names.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

We also saw a lot of the peak rushrose, Helianthemum scoparium. It is a California native species that does well in dry, sandy areas, such as throughout most of Fort Ord.

While I was leaning down to photograph this plant, one of the Reserve volunteers pointed out a much paler version nearby. He told me that most of the time the peak rushrose has brilliant yellow flowers, but there are always a few that have this much more delicate color.

12 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

And speaking of yellow, I discovered another new-to-me organism! What at first glance looked like a blotch of spray paint on a tree trunk turned out to be something much more interesting–a gold dust lichen in the genus Chrysothrix.

The lichen book1 that I have describes two species of Chrysothrix, both of which can be found in coastal regions of California. The species have some overlap in habitat, with C. granulosa usually living on bark and occasionally on wood or rock, while C. xanthina can regularly be found on bark, wood, and rock. Nor is color by itself an entirely useful characteristic: C. granulosa is described as brilliant yellow, and C. xanthina can be brilliant yellow, yellow-green, or yellow-orange. There are certain tests that would be able to distinguish between the species, but field ID when the lichen is ‘brilliant yellow’ remains problematic. So while I’d guess that this specimen is Chrysothrix granulosa (based on a combination of color, location, habitat, and good old-fashioned gut feeling) I can’t be at all certain.

The discussion of lichens brings us around to the animals. Did you know that fungi are more closely related to animals than they are to plants? Well they are, despite being included in more botany than zoology courses. And of course we did see animals on our plant hike. Hawks and turkey vultures soared overhead, song birds and hummingbirds flitted among the trees and shrubs, alligator lizards mated, and there was that one rattlesnake, which even the people on the herps walk didn’t get to see. As we hiked through the various plant communities in the Reserve, Joe occasionally called out “If you see a horned lizard, catch it!” A woman in our group, Yvonne, managed to do so, despite being loaded down with a backpack and a camera. She pounced on it and held it up for us to photograph.

Cute little thing, isn’t it?

The last critter we saw as we were walking back to the gate after lunch was a juvenile gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer). By the time I got there the snake was resting in the road. It was a very pretty snake. I wanted to take it home and release it into my yard, where there are enough gophers to feed an entire family of snakes, but alas, collecting is not allowed at the Reserve. I do wish that a gopher snake would move into my yard, though.

It is now about 24 hours since we got home. We did our tick checks and didn’t find anything, thank goodness, then showered and scrubbed. There’s no doubt that we were both exposed to poison oak; it is impossible NOT to be, this time of year. This is the real test for whether or not I am allergic to it. I haven’t been so far, but there’s a first time for everything and I will never say that I will never get it. My husband, who gets poison oak very easily and very badly, says it could take up to two days to be sure. I’m not itchy today. Tomorrow may be a different story, though.

1Sharnoff, S. 2014. A Field Guide to California Lichens, Yale University Press