Earlier this week an acquaintance asked me about the development of sand dollars, specifically if it is anything like that of sea urchins. It just so happens that sea urchins and sand dollars, while not in the same taxonomic family, are in the same class, the Echinoidea. As close kin, they share a similar larval form, the pluteus larva, and undergo more or less the same development. If you’re satisfied with the short answer, you can stop reading here.

Interested in the details? Then read on!

In my first year of graduate school I took a course in comparative invertebrate embryology through the University of Washington up at the Friday Harbor Lab in Puget Sound. It was a blast! We spent mornings in lecture and afternoons in the field and/or in the lab observing and drawing embryos and larvae. At night we would lie on our bellies on the dock and shine a light over the water, scooping up the critters that rose to the surface. It was in this class that I did my first studies of larval development and fell in love with the echinopluteus. In that class we studied several echinoid species, but the only one I was able to follow all the way through to metamorphosis was the sand dollar Dendraster excentricus.

Even a casual beachcomber has likely encountered the naked tests of dead sand dollars, but I’d bet that most people haven’t seen them alive. The bare test is white, while in life the animal is a fuzzy grayish-purple color. As their name indicates, they live on sandy bottoms in the shallow subtidal, where they prop themselves in the sand and catch particles of food that fall on them. This photo below is of the sand dollar exhibit at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. My friend, Chris Mah, is the owner of the most excellent Echinoblog and has explained how sand dollars really are sea urchins. Check it out for some good information from a real-life echinodermologist (yes, I just made up that word).

But the original question I was asked to address is about the development of sand dollars as it compares to that of sea urchins. Given that these animals share the same larval form, you would probably not be surprised to learn that their overall development is very similar. Just to remind myself of exactly how similar, I dug through my old embryology notebook and took pictures of some of my drawings. Keep in mind that these drawings were intended to document my observations, not to be pretty or artistic. However, they may be useful as comparisons with the photos of sea urchin larvae that I’ve been taking over the years.

© Allison J. Gong

According to my notes, to speed up development we cultured these larvae at room temperature so we could get through the entire larval period in the 5-week course. I didn’t record the temperature, but would guess it to be about 17ºC. At this temperature it took the Dendraster larvae only two days to get to the early pluteus stage, complete with functioning gut and skeletal rods (see drawing on right).

In contrast, the Strongylocentrotus larvae that I started this past January were still forming their guts at the ripe old age of 2 days. You’ll have to take my word for that, as I didn’t take pictures. I do have a photo of the embryos when they were 1 day old and had just hatched:

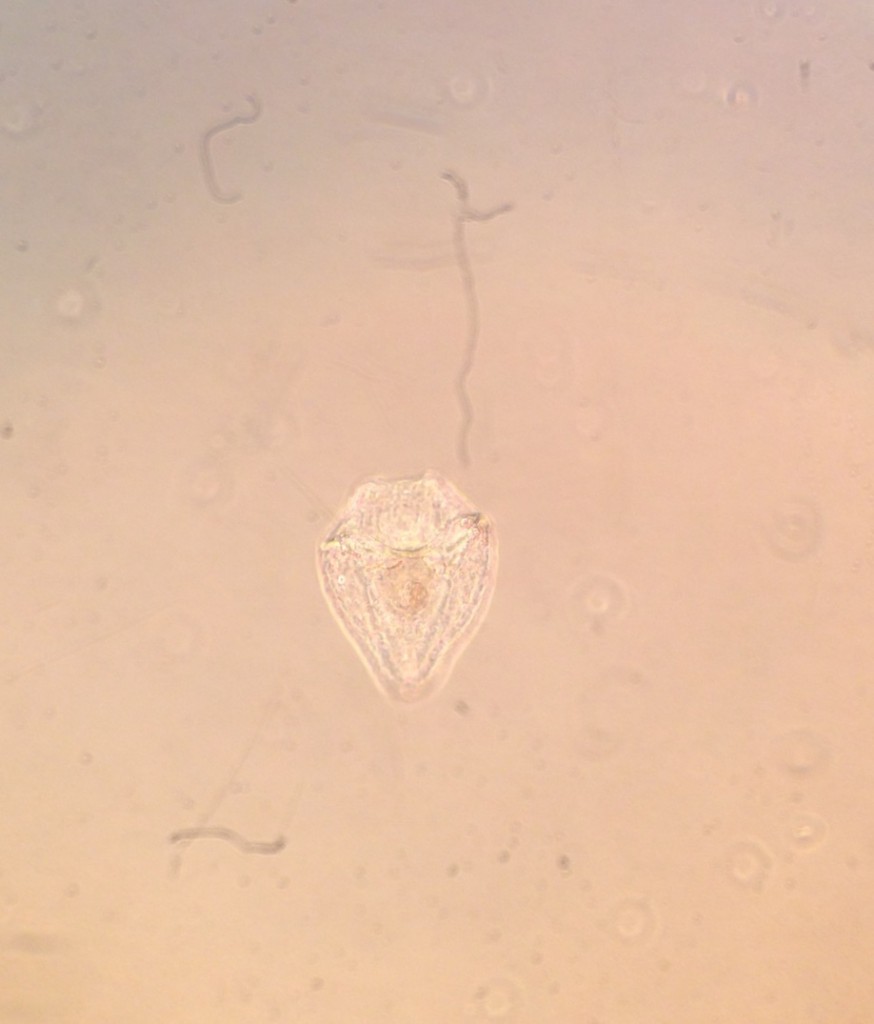

By the age of 7 days, the Dendraster larvae already had three pairs of fully developed arms (the anteriolateral, postoral, and posterodorsal arms), with the fourth and final pair (the preoral arms) just beginning to form:

The Strongylocentrotus larvae, on the other hand, had barely started growing their first arms at 6 days of age:

After a few weeks the Dendraster larvae had grown all four pairs of their arms as well as their juvenile rudiment on the left side of the gut. The individual I drew has a fully formed rudiment with five tube feet (labelled ‘podia’ in the drawing) and an additional waviness to the ciliated band (shaded in the drawing). My guess at the time was that this individual was developmentally competent, or ready to settle out of the plankton and metamorphose.

Most of the sea urchin larvae had not even started forming rudiments by the age of 31 days:

When I was in Friday Harbor I was lucky to see one of my Dendraster larvae undergo metamorphosis more or less as I was watching under a microscope. I wish I’d had the set-up to take microscope pictures, because it was an amazing phenomenon to observe. I did make one last drawing of the newly metamorphosed and benthic tiny sand dollar and its discarded larval skeletal rods:

I’m sure that I drew what I saw, but looking at this drawing with more experience I wonder if the tube feet really looked like that. Oh well. One of the last things we did as a class was “graduate” our remaining larvae off the dock and wish them luck as we released them into the real world.

With my most recent batch of S. purpuratus larvae, I began seeing competence at 45 days post-fertilization. The first bona fide juvenile urchin didn’t begin crawling around on tube feet until 50 days:

The next logical question would be: Why do the sand dollars develop so much more quickly than the urchins? I don’t have a definitive answer for that. Since that class in Friday Harbor I haven’t had another chance to study sand dollars, but in my experience my most recent cohort of sea urchins progressed through development at the normal pace for the species in this location. Some species just take longer than others, and the differences could be due to any number or combination of factors: water temperature, genetics, presence or absence of settling cues, water chemistry, and so on. The take-home message, if you’ve managed to read this far, is that yes, sand dollars and sea urchins undergo pretty much the same development. It’s the same as the short answer at the top of the post, but wasn’t it fun getting there the long way?