After much teasing and titillation, my urchin larvae have finally gotten down to the serious business of metamorphosis. It seems that I had jumped the gun on proclaiming them competent about a week ago, or maybe they were indeed competent and just needed to wait for some exogenous cue to commit to leaving the plankton for good. In any case, I’ve spent much of the last five days or so watching and photographing the larvae to document the progress of metamorphosis as it occurs. While I was unable to follow any individual larva through the entire process of metamorphosis, I did manage to put together a series of photographs that document the sequence of events.

To recap: A competent larva is anatomically and physiologically prepared to undergo metamorphosis. This batch of larvae reached competence at the age of about 45 days. The larva below is very dense and opaque in the main body. It can still swim, but has become “sticky” and tends to sit on the bottom of the dish.

© Allison J. Gong

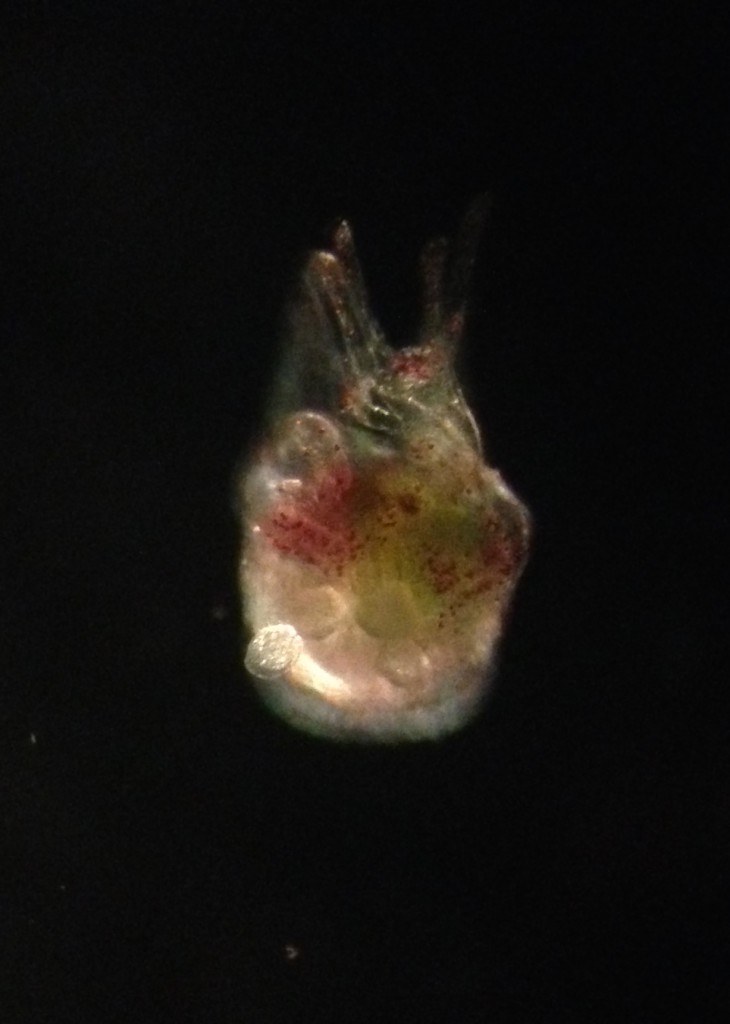

Sometimes the first tube feet emerge from the larva while it is still planktonic. Other times the larva falls to the benthos and lands on its (usually) left side, where the rudiment is located.

This larva is lying on its right side, so the tube feet are sticking straight up out of the plane of view. You can clearly see two of them, though.

© Allison J. Gong

Just for kicks, here’s the same larva, photographed with dark-field lighting. This kind of light illuminates the surface of the object being viewed, which is very helpful when the subject is opaque, making it possible to see four tube feet in this picture.

© Allison J. Gong

As the tube feet are emerging from the juvenile rudiment, the larval body contracts and gets denser. The arms shrink and the internal skeletal rods that supported them are discarded. At this stage the larval juvenile (larvenile? juvenal?) begins to crawl around on the bottom. The ciliated band that used to propel it through the water and create the feeding current may still be beating, but eventually will stop, as the larvenile will no longer need it. This is usually the time that I see the first spines waving around; it’s interesting to note that tube feet, which originate from the inside of the animal, come first, then are followed by spines. Then again, the spines are part of the animal’s endoskeleton, so maybe it’s not so noteworthy after all.

© Allison J. Gong

So they’re getting close to becoming real urchins! Next up: Learning to walk.

Did you notice that I invented a new word? I’m going to start using it regularly.

Hello, Allison.

Looking for S. purpuratus larvae pictures I came across your blog, and I have to say your organisms and pictures are pretty good. The reason I was looking for pictures is because I’m doing my thesis, working on S. purpuratus larvae, but just at the 4-arms stage, and I wanted to have some pitures of other stages just to ilustrate their developmen in real life instead of drawings, so i was wondering, would you let me use some of your pictures? particularly, the 6-arm stage since it’s the harder to get, but also of the other late stages?

Thankyou, in advance. Have a nice day.

Hello Damian,

Can you tell me a bit more about what your thesis research involves? Are you growing the S. purpuratus larvae yourself?

Allison

Ah, hello.

Sure. My thesis is about the effect of ocean acidification on larvaes, meassuring sizes and the expression of certain genes related to calcification. I grew some larvae, in different pH waters, but only at the 4-arms stage, so I don’t have pictures of late stages. Since it’s an ecological work, and related to the life cycle of the organisms, I wanted to also illustrate how they change as they develop/grow older.

Sounds very interesting. I know that someone has looked at the effects of acidification on larval development and survival, but don’t know whether or not anyone has investigated what happens to larvae exposed to lower pH when they metamorphose.

You may use any of my photos, provided that my copyright information remains with them and I am credited as the creator and owner of the photos.

Good luck with your thesis work!

Thank you very much. Of course, I will give you credits on my work. Do you preffer if I use your name and site to credit you, or should I mention any other Institution?

That’s a good question. Something like this should work:

© Allison J. Gong (year)

Institute of Marine Sciences

University of California, Santa Cruz

Used with permission