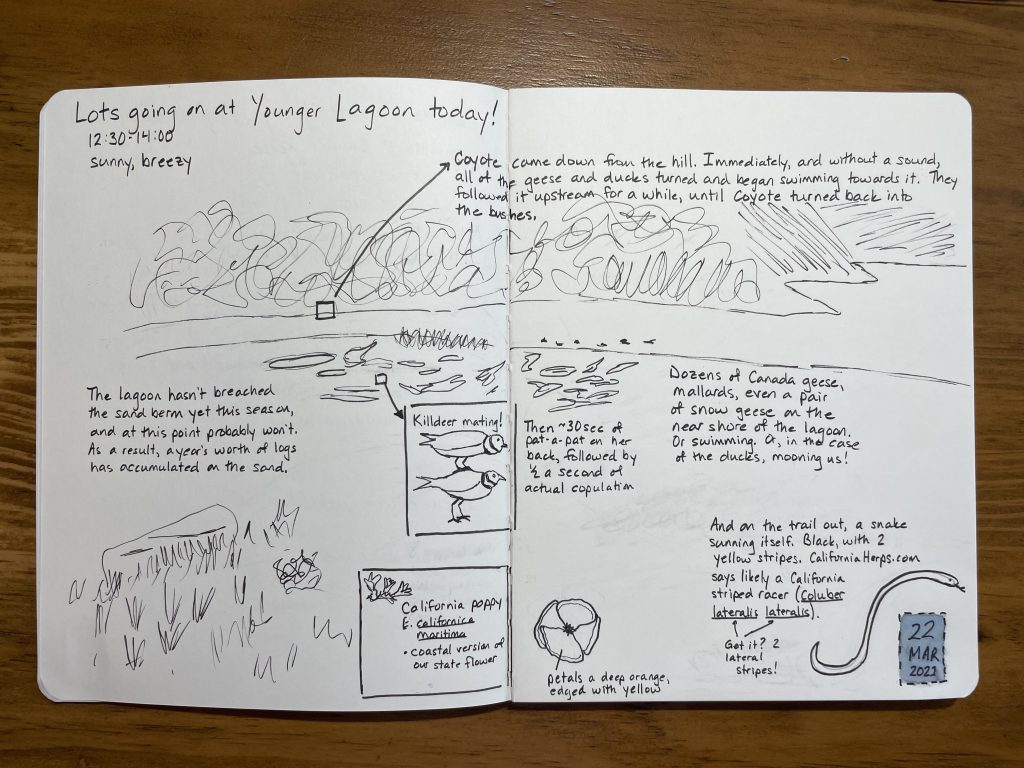

The other day I was on a field trip with a couple of students in the Natural History Club, at Younger Lagoon. We had permission to go down into the lagoon itself, where we chased tiny red mites around rocks in the intertidal without getting caught by waves, observed a very interesting interaction between a coyote and assorted water fowl, and witnessed killdeer mating. Did you know that in killdeer the actual copulation is preceded by about half a minute of massage? Neither did we! The purpose of the field trip, other than merely to be outdoors looking at cool stuff, was to spend some time doing focused nature journaling. As a result I didn’t have my big camera with me. But I did have the good binoculars, and got to watch all of the action closely.

Nature journaling should be part of any natural history club. Over the years I have seen an increase in the tendency to equate nature journaling with science illustration or other types of art. This conflation is what causes people to believe that they can’t keep a nature journal because they don’t produce museum-quality works of art. While I appreciate a beautiful science illustration as much as anybody else, a nature journal serves a completely different purpose. A nature journal’s job isn’t to be beautiful. Its job is to be informative.

If you were to compare my nature journal entry with a photograph of the site, you would see that my sketch is nowhere near realistic in the sense of looking exactly like the real thing. I’ve compressed the entire lagoon into a short stretch that I could fit in these two pages. But I think the sketches and notes do convey the fascinating things what we saw that day. And even if I were not familiar with Younger Lagoon, I would be able to look at these pages and remember them. That’s the job of a nature journal.

I returned to Younger Lagoon two days later with the camera in tow, hoping that some of the birds we’d seen on Monday would still be there on Wednesday. In addition to the usual Canada geese and mallards, I hoped to shoot a couple of water birds that I didn’t recognize.

Let’s start with the obvious:

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

All told, there were a couple dozen Canada geese, in the water, in the air, and on the sand. They were a noisy bunch, as usual. Except for when the coyote showed up. Read that little story in my nature journal.

Now take a look at these geese:

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

See the one goose that doesn’t belong? That was the mystery goose I saw on Monday, and was fortunate enough to see again on Wednesday. From the photos in my bird field guide—National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America—I thought it might be a greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons), although I couldn’t be entirely certain. I knew I hadn’t seen one before, but a consultation with Cornell’s All About Birds verified the ID. iNaturalist shows only a handful of observations of A. albifrons in the Monterey Bay region. The greater white-fronted goose is a long-distance migrator, breeding on the tundra of the high Arctic and overwintering in California’s Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys and the Gulf coast of Texas and Louisiana.

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

A third goose, and another winter-only bird, is the snow goose. It is a little bigger than the greater white-fronted goose. While the word “snow” implies white plumage, snow geese also come in a blue form, which is a dark blueish gray with a white head. The blue coloration is due to a single gene, and the allele for blue is incompletely dominant over the allele for white. The blue and white morphs are the same species and interbreed freely. The offspring of a pure blue bird and a pure white bird will be dark, but may have a white belly. Goslings from pure white parents will be white, and those from pure dark parents will be mostly dark but may have some white.

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

Of the two snow geese in the photo, the one in the front is all white except for the black wing tips of the species, while the one in the back has more dark coloration. In the photo the beak looks dark, but in better light it’s as pink as on the bird in the front.

So that’s three species of geese. Now whose butts are these?

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

These tails belong to American wigeons (Mareca americana), a male and female pair in the background and a lone male in the foreground. As you might guess from the behavior, wigeons are dabbling ducks, foraging on aquatic vegetation. Like the greater white-fronted goose and snow goose, these are also winter visitors to California’s waterways, and will soon be headed north.

In their winter plumage, the wigeons are rather dull. The breeding male has a brilliant green patch extending backwards from his eye and a broad white streak from the top of the bill over his head. During the winter the green patch becomes is much less conspicuous, although the white streak remains.

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

Three species of waterfowl. I couldn’t get the snow geese to cooperate and make up the quartet.

2021-03-24

© Allison J. Gong

Living as we do along the Pacific flyway, we find that spring and autumn are great times for watching birds as they migrate between summer breeding grounds and wherever they overwinter. Sometimes I think it’s rather unfortunate that I don’t get to see these birds in the glory of their breeding plumage, but that’s okay because I get to see them in the winter. And the birds that left here for the winter are returning: I saw the first barn swallow of the season right after the vernal equinox! Soon they and the cliff swallows will be building their nests on the buildings at the marine lab. At home, the first of the season’s hooded orioles flew past the back deck. He may have been on his way to a nesting site in a palm tree down the street. There is so much going on right now. I do love the spring!