People who moved here from other states often say that California doesn’t really have seasons. I think what they mean is that in general we don’t oscillate between frigid winters and hot, humid summers. The Pacific Ocean moderates weather conditions through most of the state, giving us our Mediterranean climate characterized by a short rainy season and a long dry summer. However, California is a very large state with many different climate zones. Here on the coast our summers are cool and foggy, while in the interior of the state summers can be quite hot, upwards of 38° C for weeks at a time. Snow falls in the Sierra Nevada, providing much of the state’s annual water budget, but the rest of the state usually remains snow-free for most of the winter.

That said, California does of course have seasons, even though they may not be as in-your-face as what you’d see in, say, New England. One of the ways to experience the seasons is to observe the comings and goings of migratory wildlife, especially birds. In fact, bird migration patterns make up a significant part of phenology, the study of the timing of biological events in the natural world. California’s position along the Pacific Flyway provides fantastic bird watching opportunities throughout the year. There are many locations within California that are pit stops for birds migrating up and down the coast and overwintering oases for birds that breed much farther north.

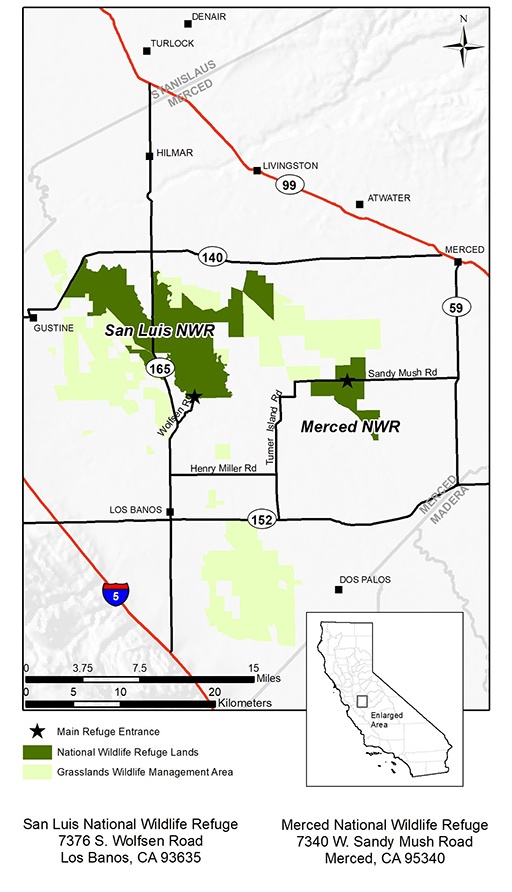

The San Luis National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in Merced County is one such place. Located in the Central Valley, it represents some of the original habitat in this part of the state. The San Joaquin River winds through the Reserve, providing riparian habitat, although the river is currently a mere ghost of its former glory. Since 2009, federal and state entities have worked to restore the San Joaquin, increasing water flows and cleaning up the surrounding lands. While it would be marvelous to see chinook salmon once again migrating from San Francisco Bay up the San Joaquin, it hasn’t happened yet. The re-establishment of salmon runs up to just below Friant Dam would indicate a healthy San Joaquin River, and I really hope to see it in my lifetime.

Before the era of modern agriculture, much of the Central Valley flooded with the winter rains and spring snowmelt. Only a tiny fraction of these wetlands remain; most have been drained for agriculture and further deprived of water by state and federal water diversion projects. In areas such as these, small pools form during the wet season. These vernal pools–so called because they are often at their deepest during the spring–are ephemeral habitats. They almost always disappear during the long dry summer, but during their short existence they provide living space for a unique biota. A few vernal pools occur in most of the flat areas of California, although there are far fewer of them than before, and they differ biologically throughout the state. It is not uncommon for each vernal pool in a given area to have its own combination of flora and fauna, all of which have adapted to thrive in both desiccated and flooded conditions.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

On our way back to the coast after spending Christmas with my family, we stopped at the San Luis NWR to do some wildlife watching. The visitor center was closed because of the federal government shutdown, but the roads were open. The Refuge has two auto tour routes, one to the tule elk reserve and the other to see resident and visiting aquatic birds. We chose to drive the bird route, because winter is a good time to see birds that spend the rest of the year at much higher latitudes.

© Allison J. Gong

Coots (Fulica americana) are ubiquitous in California’s wetland habitats, and because of that they are easily overlooked. When I was little we called them ‘mudhens’ and smirked at them because they weren’t ducks. Of course I now realize that that thinking is entirely unfair, and have come to appreciate coots because they aren’t ducks.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

In addition to the coots, which weren’t much of a surprise because we expected to see them, we saw large numbers of several species that we weren’t as familiar with. There were ducks and geese, which took us some time to ID because they weren’t mallards and Canada geese. Fortunately I keep a bird field guide and binoculars in the car! My favorite bird ID book is the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America; we keep one of the later editions at home, but my beloved and well battered third edition lives in the glove compartment.

The ducks turned out to be northern shovelers, which I’ve seen at Elkhorn Slough. True to the typical avian way of doing things, the males are strikingly colored, with brilliant green heads, while the females are a dark streaky brown. In the photo below, a female swims with two males.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

The geese were entirely new to us. We first saw them flying overhead in the V-shaped formations that you expect from a gaggle of geese in the air. But they didn’t honk like Canada geese so we knew right away that they were something different.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

I wasn’t able to ID these until we got home and I looked at my photos on the computer. iNaturalist helpfully gave me a tentative ID of greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons), which I was happy to go along with.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

In North America, greater white-fronted geese nest in the Arctic of western Canada and through most of Alaska, including out along the Aleutians. They migrate south to spend the winter along the Gulf coast and along the eastern coast of the Sea of Cortez. The winter wetlands of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys host many of these geese, and smaller numbers overwinter in coastal Oregon and Washington.

Living in California, I don’t usually expect to encounter any species whose common name includes the word ‘tundra’, but tundra swans do indeed spend their winters here! They nest in the very high Arctic on tundra, a habitat that is threatened by climate change, and winter is the only time we would see them in the lower 48, when large flocks venture south to overwinter near lakes and estuaries. I’ll keep an eye out for them next time I’m at Elkhorn Slough or Moss Landing.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

We saw hundreds of these swans hanging out with the shovelers. Only a few were within photograph range, as I don’t have a very long telephoto lens (yet!), but there were lots of large white blobs floating, foraging, preening, and sleeping. They were fun to watch through the binoculars. We had hoped to see some sandhill cranes in the Refuge, too. We had seen them off in the distance, much too far to be photographed, but it wasn’t until we were on the last leg of the auto tour that we saw them up close. They were not mingling with the swans and geese, and as far as we could tell tended to gather in single-species flocks. They seemed to be more skittish, too, and would startle and fly away when they heard human noises. I had to move slowly and quietly to get this close to them. Even the sound of the camera shutter caught their attention and made them wary.

2018-12-26

© Allison J. Gong

The Central Valley is Ground Zero for sandhill cranes in California, where they can be seen only in the winter. They don’t breed here, of course, but there is a small population of ~460 pairs of sandhill cranes breeding in far northeastern California. There are locations in the Central Valley that are known for hosting large crane populations in the winter, and one of my goals is to witness a big ‘fly-in’ event, when huge flocks come in to roost in the evening. I’ve seen pictures, and it looks like a spectacular sight. I want to see it with my own eyes.

All this is to say that we do indeed have seasons in California. The shifts between summer and winter are perhaps more subtle here than in other states, but an observant eye keeps track of changes in the natural world. And you don’t have to be a trained scientist to track seasonal changes wherever you live, either. We tend to use temperature to tell us which season we’re in, but in reality light is a much more reliable indicator. Just think of how dramatically temperature can fluctuate in a few days, and how much more extreme these fluctuations seem to be in recent years, due to climate change. Day length cycles, however, remain constant over geologic time, as we humans haven’t yet figured out a way to mess with the tilt of the earth’s axis. Everyone notices how the amount and quality of light change with the seasons. It takes just a little more effort to notice the ways that life responds to those changes.