The marine macroalgae, or seaweeds, are classified into three phyla: Ochrophyta (brown algae), Rhodophyta (red algae), and Chlorophyta (green algae). Along the California coast the reds are the most diverse, with several hundred species. The browns have the largest thalli (the phycologists’ term for the bodies of algae), including the very large subtidal kelps as well as the smaller intertidal rockweeds. The green algae are small in both thallus size/complexity and species diversity; many of the greens are filamentous and look like nothing more than slime growing on rocks or other surfaces.

On the other hand, what appears to be simple at first glance can turn out to be delightfully complicated and puzzling upon closer examination. Take, for example, the two species of green algae in the genus Codium that occur intertidally in northern California: Codium setchellii and C. fragile. Codium setchellii is a native species here. It grows as a thick rugose mat over rocks in the mid-intertidal. Its color is a very deep olive green, but when dry it looks almost black.

Codium setchellii has a smooth texture and feels like very thick velvet. It grows on vertical faces of rocks, rarely on exposed horizontal surfaces–at least, I’ve not often seen it on top of a rock. Patches of C. setchellii are usually about the size of my outstretched hand, although some can be a little larger than that. When you see C. setchellii in the field, it’s hard to imagine what type of structure would result in a thallus like this. To figure out what’s going on, you need to look at small pieces under a microscope. It’s this level of observation that reveals the filamentous nature of C. setchellii.

Phycologists have a few tricks for observing the internal structure of algae. The firm-bodied algae can be examined via cross-section, which can be more or less difficult to make depending on the species. Many simpler thalli, however, can be examined by making a squash, which is exactly what it sounds like: You take a piece of the alga, place it in a drop of water in a slide, and squash it with a cover slip.

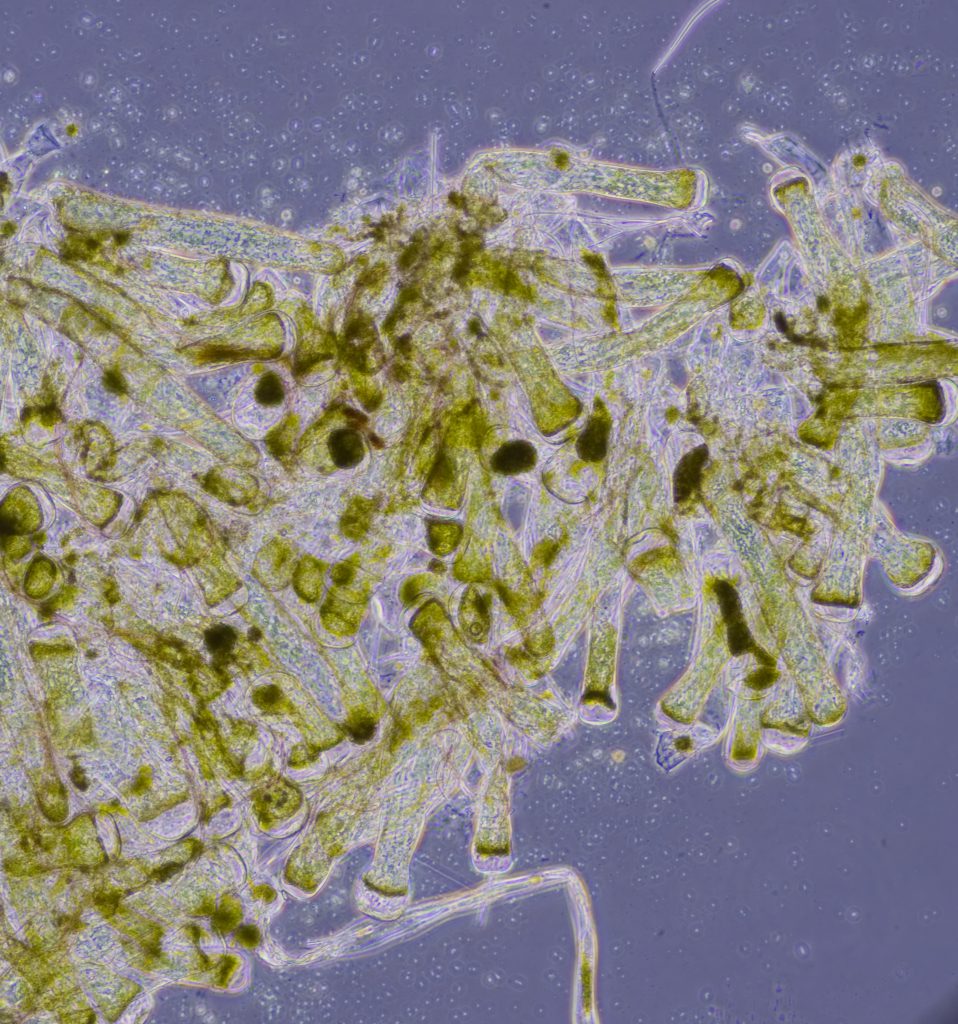

A squash of C. setchellii revealed this mishmash of filaments:

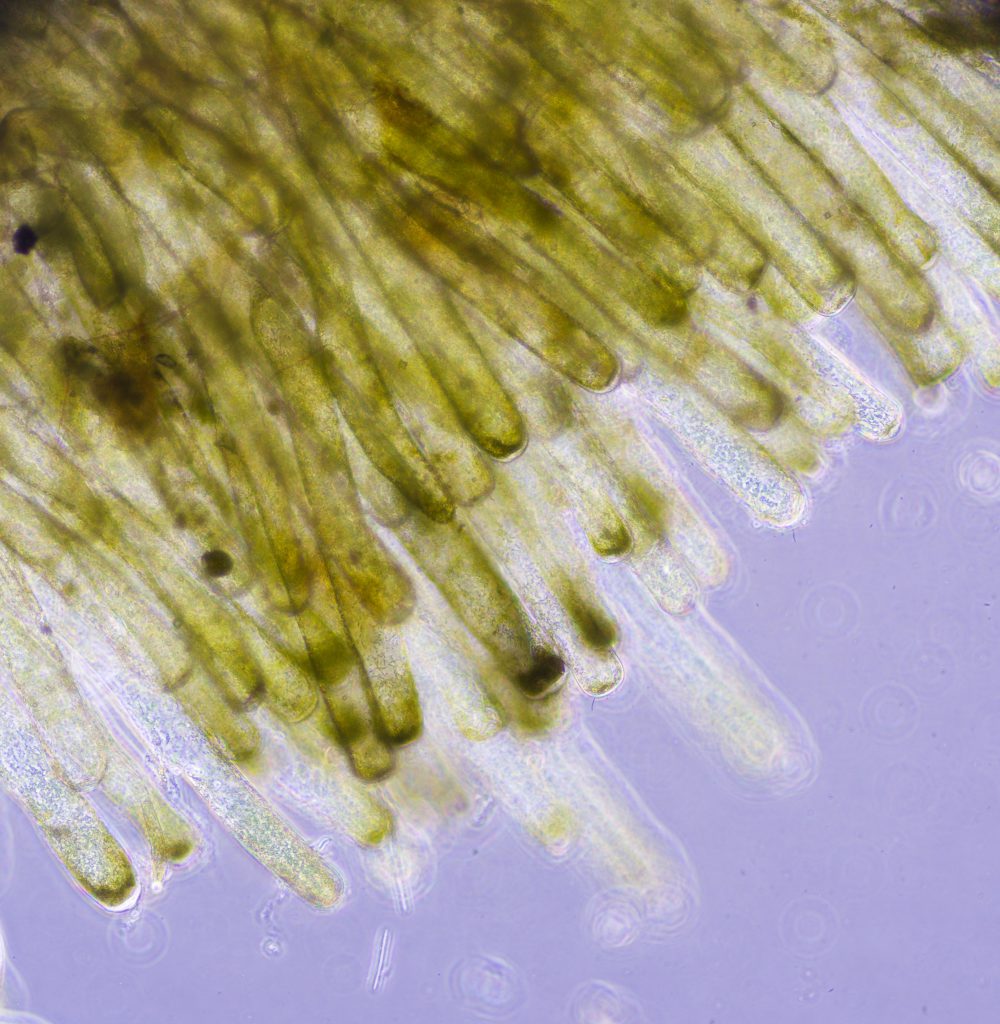

This particular squash shows the utricles, which are the pigmented ends of the filaments. It didn’t really help me understand how the filaments are organized within the thallus, though. I even tried making a cross-section of the little piece of C. setchellii I have, but it turned to mush. I did at least get one squash that showed the filaments to be arranged in approximately parallel fashion at the outer edge of the thallus.

So, seeing the internal structure of Codium setchellii allows me to understand how its closely packed filaments produce the velvety cushion of the thallus that I see in the field. The way that the filaments are aligned allows them to be tightly packed together, resulting in a cushion that is surprisingly firm rather than squishy.

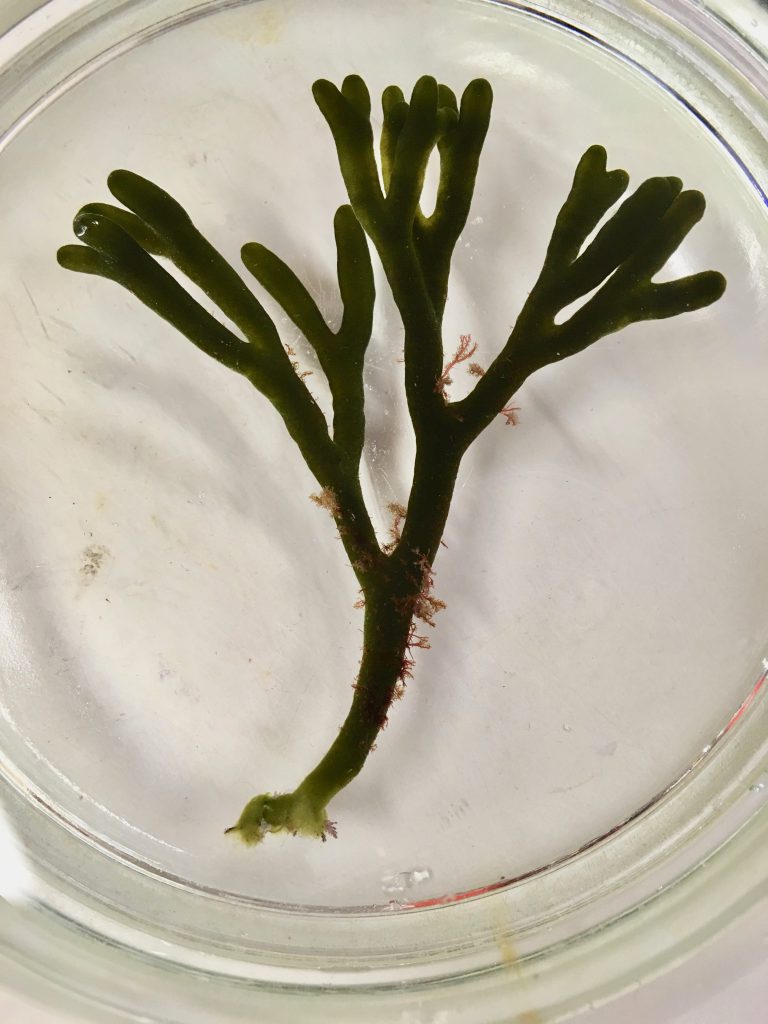

The second species of Codium that we see in northern California is C. fragile, commonly called ‘dead man’s fingers’. It is a non-native species here, originating in the western Pacific near Japan, and has spread into the Atlantic. In California it has a patchy distribution and, in my experience at least, isn’t as common as C. setchellii. I have never seen the two species together at the same site, but according to iNaturalist they do co-occur in some locations.

Like its congeneric species, C. fragile is a dark greenish color and lives in the mid- to low-intertidal. But otherwise it looks entirely different. The thallus morphology must be what gave rise to the common name. I remember learning years ago about a seaweed called ‘dead man’s fingers’ and being disappointed when I saw it for the first time. It didn’t look like dead man’s anything!

This thallus resembles a clump of approximately dichotomously branching tubes. It is spongy in texture and is often colonized by bits of a filamentous red alga.

In this case, the red alga (Ceramium sp.) is in turn colonized by the benthic diatom Isthmia nervosa:

19 July 2018

© Allison J. Gong

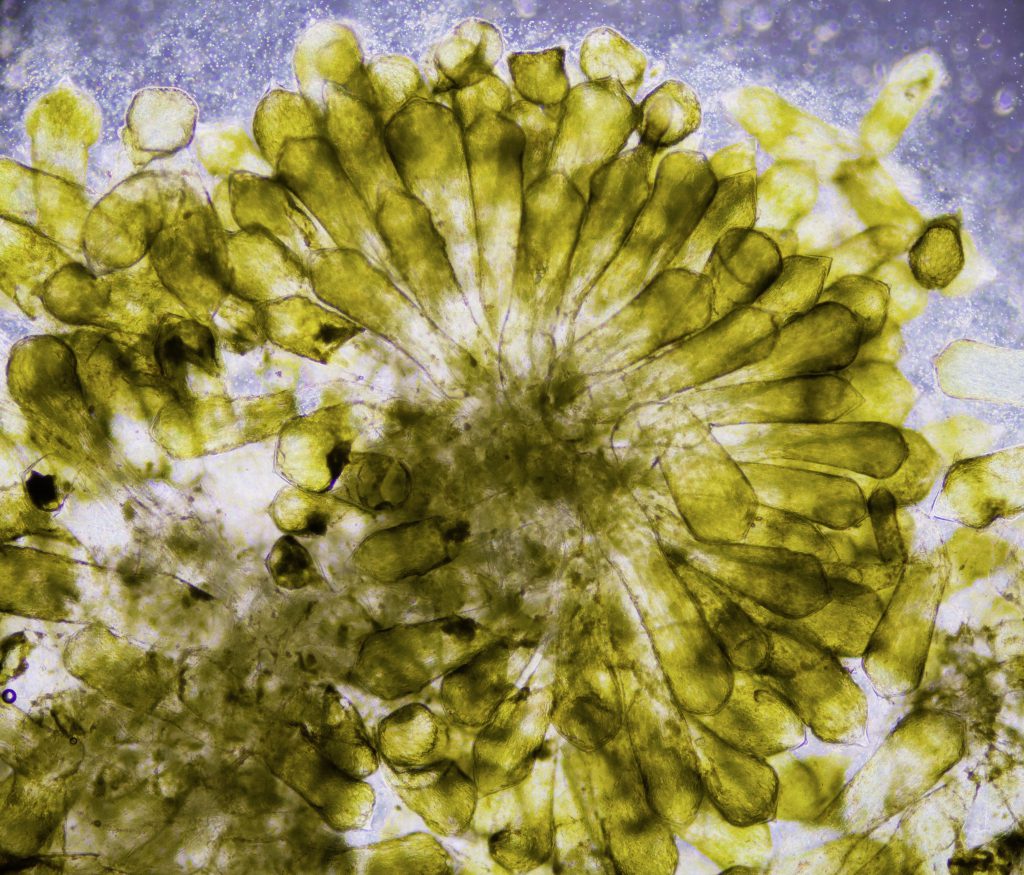

You might expect Codium fragile, having a tubular morphology, to be more amenable to being examined in cross-section. I can tell you that that isn’t the case. It’s easy enough to make the first transverse slice of one of those ‘fingers’, but the second slice, even made with a brand new razor or scalpel blade, results in a pile of mush. I made and looked at several such piles, hoping that at least one would show an approximation of the cross-sectional anatomy of this thallus. The best I could get was this:

At least it shows the radiating arrangement of the filaments. I think this is really interesting. The utricles (pigmented tips of the filaments) are a bit thicker than the unpigmented section of the filaments that make up the interior of the cylinder, but there’s still space between them at their distal tips. It is this arrangement that gives Codium fragile a squishiness that C. setchellii lacks.

So there you have it. One genus, two species with radically different gross morphology but similar internal morphology. They’re made of the same types of cells, at least. Like I said, I’ve not seen them in the same place in the field, but here in my blog you can see them side by side.