When low tides occur at or before dawn, a marine biologist working the intertidal is hungry for lunch at the time that most people are getting up for breakfast. And there’s nothing like spending a few morning hours in the intertidal to work up an appetite. At least that’s how it is for me. Afternoon low tides don’t seem to have the same effect on me, for reasons I can’t explain. A hearty breakfast after a good low tide is a fantastic way to start the day.

Sea anemones are members of the Anthozoa (Gk: ‘antho’ = ‘flower’ and ‘zoa’ = ‘animal’). These ‘flower animals’ are the largest cnidarian polyps and are found throughout the world’s oceans. They are benthic and sedentary but technically not sessile, as they can and do walk around, and some can even detach entirely and swim away from predators. The anthozoans lack the sexual medusa stage of the typical cnidarian life cycle, so the polyps eventually grow up and have sex. In addition to the sea anemones, the Anthozoa also includes the corals, sea pens, and gorgonians.

With their radial symmetry and rings of petal-like tentacles, the sea anemones do indeed resemble flowers. You’ve seen many of my anemone photos already. Here’s one more to drive home the message.

Sea anemones are cnidarians, and cnidarians are carnivores. Most of the time anemones in the genus Anthopleura feed on tiny critters that blunder into their stinging tentacles, although the occasional specimen will luck into a much more substantial meal. I’ve watched hermit crabs crawl right across the tentacles of a large anemone (Anthopleura xanthogrammica), and while the anemones did react by retracting the tentacles, the crabs easily escaped their grasp.

Of course, not all potential prey items are so fortunate. Sometimes even big crabs get captured and eaten, like this poor kelp crab (Pugettia producta):

8 March 2017

© Allison J. Gong

There’s no way to know exactly how this situation came to be. Was the crab already injured or weakened when the anemone grabbed it? Or was the anemone able to attack and subdue a healthy crab? I’ve always assumed that the exoskeleton of a crab this size would be too thick for the rather wimpy nematocysts of an Anthopleura anemone to penetrate, but maybe I’m wrong. A newly molted crab would be vulnerable, of course; however, they tend to stay hidden until the new exoskeleton has hardened, and the crab in the above photo doesn’t appear to have molted recently.

Even big, aggressive crabs can fall prey to the flower animals in the tidepools. I’d really like to have been there to watch how this anemone captured a rock crab!

17 June 2018

© Allison J. Gong

And crabs aren’t the only large animals to be eaten by sea anemones. Surprisingly, mussels often either fall or get washed into anemones, which can close around them. Once a mussel has been engulfed by an anemone, the two play a waiting game. Here’s what I imagine goes on inside the mussel: The bivalve clamps its shells shut, hoping to be spit back out eventually; meanwhile, the anemone begins trying to digest the mussel from the outside; sooner or later the mussel will have to open its shells in order to breathe, and at that point the anemone’s digestive juices seep inside and do their work on the mussel’s soft tissues. When the digestive process is finished, the anemone spits out the perfectly cleaned mussel shells.

17 June 2018

© Allison J. Gong

In the photo above, the anemone is working on a clump of several mussels. I can’t see that any of these mussels have been compromised, but the pale orange stringy stuff looks like mussel innards and slime. It could be that several mussels are still engulfed within the anemone. There is always a chance that an anemone will give up on a mussel that remains tenaciously closed, and spit it out covered with slime but otherwise unharmed. I assume that hungry anemones are less likely to give up their meals than ones that have recently fed.

So how, exactly, does an anemone eat a mussel, or a crab? The answer lies within the anemone’s body. Technically, the gut of an animal is outside its body, right? Don’t believe me? Let’s think it through. An animal with a one-way gut can be modeled as a tube within a tube, and by that reasoning the surface of a gut is contiguous with the outer surface of the body. Our gut is elaborated by pouches and sacs of various sizes and functions, but is essentially a long, convoluted tube with a mouth on one end and an anus on the other. Sea anemones, as all cnidarians, have a two-way gut called a coelenteron or gastrovascular cavity (GVC), with a single opening serving as both mouth and anus. Anemones, being the largest cnidarian polyps, have the most anatomically complex gut systems in the phylum.

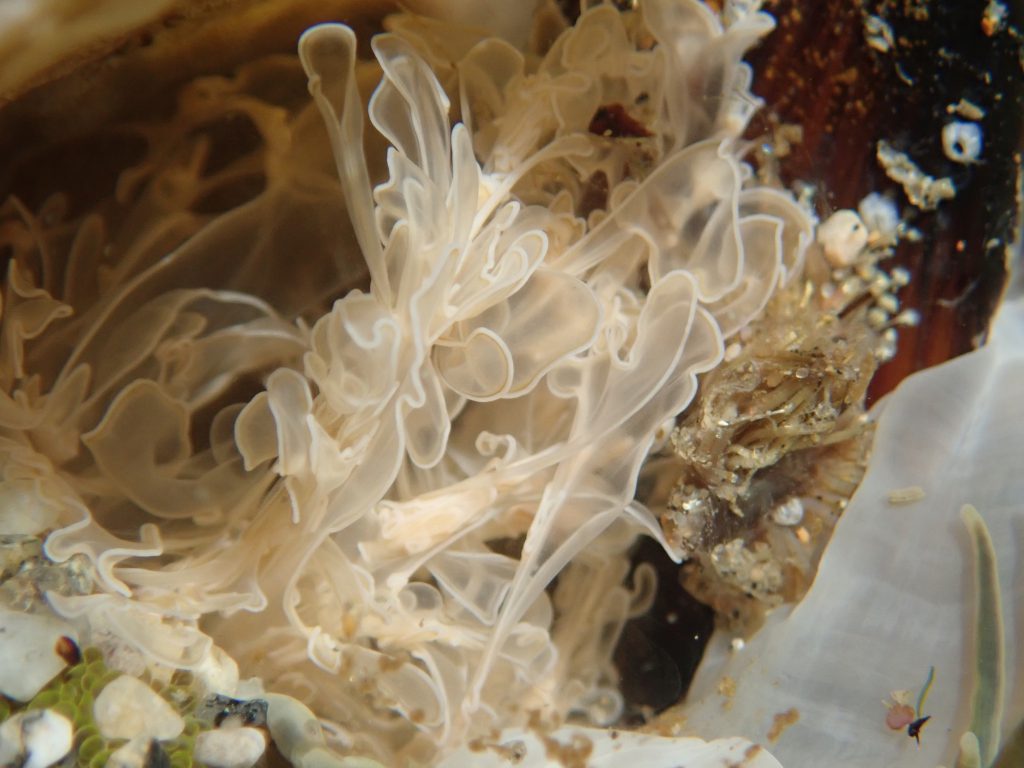

Imagine a straight-sided vase with a drawstring top. The volume of the vase that you’d fill with water and flowers represents the volume of the anemone’s gut. Anemones can close off the opening to their digestive system by tightening sphincter muscles that surround the mouth; these muscles are analogous to the drawstring closure of our hypothetical vase. Now imagine that the inner wall of the vase is elaborated into sheets of curtain-like tissue that extend towards the center of the cavity. These sheets of tissue are called mesenteries. They are loaded with various types of cnidocytes that immobilize prey and begin the process of digestion. The mesenteries greatly increase the surface area of tissue that can be used for digestion. The mesenteries are also flexible and can wrap around ingested prey to speed things up.

This anemone (below) that was eating both a mussel and a piece of kelp:

Those frilly ruffles are the mesenteries. You can see how greatly they’d increase the surface area of the gut for digestion. They are also very soft, almost flimsy. Here’s a close-up shot:

4 May 2018

© Allison J. Gong

Maybe I’m especially suggestible, but seeing these animals working on their own meals makes me hungry, too. After crawling around the tidepools for a few hours I’m always ready for a second breakfast or brunch of my own.

Bon appétit!