There are certain creatures that, for whatever reason, give me the creeps. I imagine everyone has them. Some people have arachnophobia, I have caterpillarphobia. While fear of some animals makes a certain amount of evolutionary sense—spiders and snakes, for example, can have deadly bites—my own personal phobia can be traced back to a traumatic childhood event involving an older cousin and a slew of very large tomato hornworms. Even typing the words decades later makes me want to rub my hands on my jeans.

But enough about caterpillars. This Halloween I want to share something that isn’t nearly as disgusting, but can still creep me out sometimes. Commonly called skeleton shrimps, caprellid amphipods are a type of small crustacean very common in certain marine habitats. They are bizarre creatures, but a close look reveals their crustacean nature. For example, they possess the jointed appendages and compound eyes that only arthropods have.

Around here the easiest place to find caprellids is at the harbor, where they can be extremely abundant. The last time I went to the harbor to collect hydroids for my class, the caprellids were swarming all over everything. When I brought things back to the lab I had to spend an hour or so picking the caprellids off the hydroids. I don’t think they eat the ‘droids, but they gallop around and keep messing up the field of view, making observation difficult. They’re essentially just a PITA to deal with, and everything is easier after they’ve been removed.

Caprellids are amphipods, members of a group of crustaceans called the Peracarida (I’ll come back to the significance of the name in a bit). They have the requisite two pairs of antennae that crustaceans have, and seven pairs of thoracic appendages of varying morphology. Some of these thoracic legs are claws or hooked feet that like to grab onto things. A caprellid removed from whatever it’s attached to and placed by itself in a bowl of seawater thrashes around spastically. Only when it finds something to grab does it calm down. Even then, they attach with their posterior appendages and wave around the front half of the body in what I call the caprellid dance: they extend up and forward, and sort of jerk front to back or side to side. It isn’t pretty.

A bunch of caprellids removed from their substrate and dumped into a bowl together will use each other as something to grab. This forms the sort of writhing mass that makes my skin crawl. I was nice enough to give them a piece of bryozoan colony to hang onto, but even so they ended up glomming together.

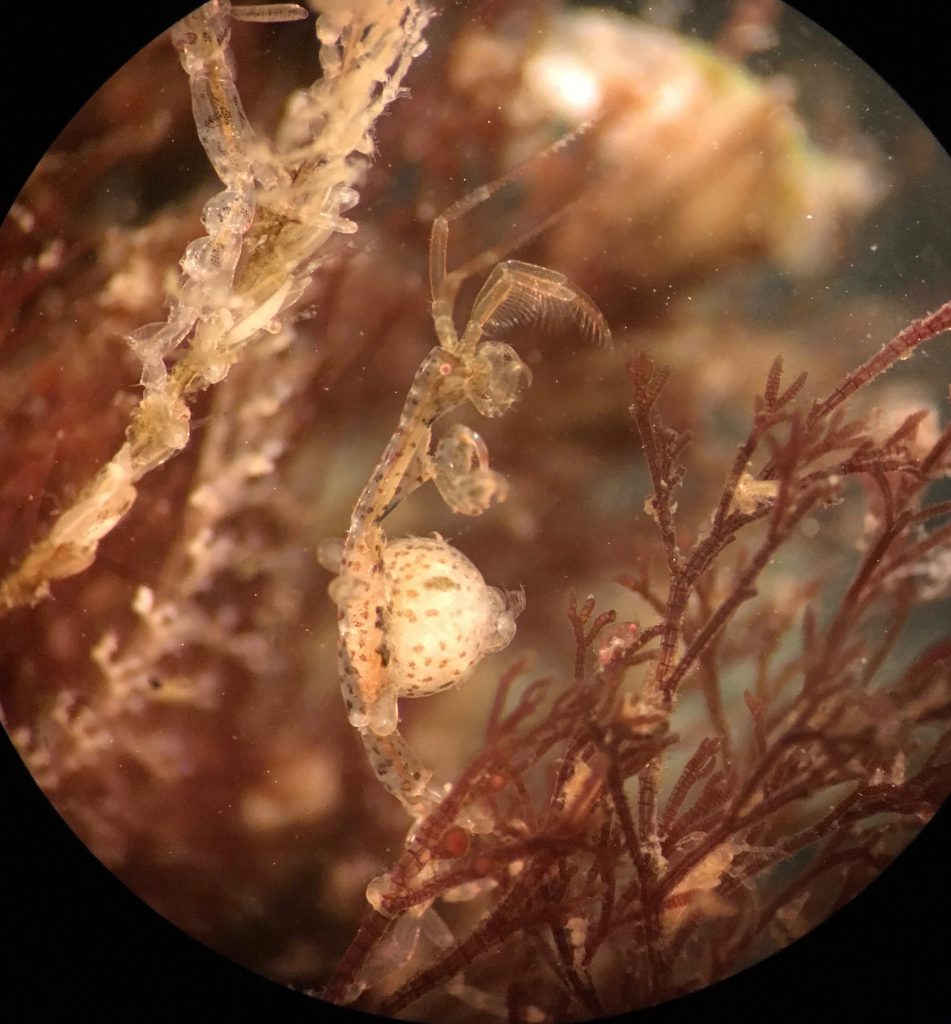

Now, back to the thing about caprellids being peracarids. The name Peracarida means “pouch shrimp” and refers to a ventral structure called a marsupium, in which females brood their young. Males don’t have a marsupium, so adult caprellids are sexually dimorphic. When carrying young, a female caprellid looks like she’s pregnant. See that caprellid in the top photo? She’s a brooding female. That’s all fine, until her marsupium itself starts writhing. This ups the creepiness factor again. Here’s that same brooding female, in live action:

Crustaceans obviously don’t get pregnant the way that mammals do, but many of them spend considerable energy caring for their young. Well, females do, at least. A female caprellid doesn’t just carry her babies around inside a pouch on her belly. Although she isn’t nourishing them from her own body in the way of mammals (each of the youngsters in the marsupium is living off energy stores provisioned in its egg), the mother does aerate the developing young by opening and closing the flaps to the marsupium. This flushes away any metabolic wastes and keeps the juveniles surrounded by clean water. As the young caprellids get bigger, they begin to crawl around inside the pouch, and eventually leave it. They don’t depart from their mother right away, though; rather they cling to her back for a while, doing the caprellid dance in place as she galumphs along herself.

Until the juveniles strike out on their own they form a small writhing mass on top of a female who can herself be part of a larger writhing mass. And the sight through the microscope of all these long skinny bodies jerking around spasmodically can indeed be very creepy. Fortunately not as creepy as caterpillars, or I wouldn’t be able to teach my class or go docking with my friend Brenna. And it’s a good thing caprellids are small, ’cause if they were any bigger. . . just, no.