This morning in the intertidal I was reminded of how often I encounter animals I wasn’t looking for and almost missed seeing at all. That got me thinking about color and pattern in the intertidal, and how they can be used either to be seen or to avoid being seen. Some critters–the nudibranchs immediately come to mind–are so brightly colored that they are impossible to miss, while others are camouflaged to the point that it takes a trained eye to see them.

Truth be told, however, most of the animals in the intertidal don’t have eyes, or at least eyes that can form images the way ours do. While just about any animal might be preyed upon by birds at low tide, most of the predators a creature of the tidepools might face would not be visual predators. This in turn begs the question of just how adaptive or not a species’ crypticness is. The way I see it, there are three options, or hypotheses about the potential benefit of an animal’s coloration and patterning:

- Colors and patterns that make an animal conspicuous are advantageous.

- Colors and patterns that make an animal cryptic or camouflaged are advantageous.

- Colors and patterns are neither advantageous or disadvantageous.

Today I’m going to consider hypothesis #2, as it is the most interesting one. Let’s put aside for now the question of how an animal’s color comes to be and consider only its effect on visibility to Homo sapiens (specifically, me).

Example #1 (obvious): Tonicella chitons

These are the pink chitons that I find on exposed coasts. They eat encrusting coralline algae, and I suspect their color derives at least in part from their diet. Here’s one that perfectly matches its food:

On the other hand, Tonicella isn’t always this entirely pink, nor is it always seen on coralline algae:

The chiton I saw at Monastery Beach wasn’t anywhere near coralline algae. It has obviously been eating something, probably algal films of whatever sort it comes across. Correlation is not causation, but it may not be mere coincidence that this pale version of Tonicella lokii lives on rock devoid of coralline algae.

Example #2 (obvious): Decorator crabs

Tonicella doesn’t intentionally alter its appearance by eating pink food. Given the extremely rudimentary nature of a chiton’s nervous system, it likely can’t intentionally do much of anything. It doesn’t have eyes so it cannot see, although there are light-sensing organs called aesthetes in the dorsal shell plates and light-sensitive cells in the lateral girdle. Chitons make their way through the world largely by following chemical gradients, either in the water current or on the substrate.

Crabs, on the other hand, have very complex compound eyes and can, to some extent, see what’s going on around them. The compound eyes of arthropods are highly effective motion sensors, certainly much more sensitive than our eyes are, which is why it’s so hard to sneak up on a fly even if you’re extending your reach by using a fly swatter. Crabs certainly are aware of the visual aspects of their surroundings. They can see potential threats and typically respond in one of three ways: (1) scuttling away; (2) coming out fighting; and (3) remaining still and trying not to be noticed.

It takes energy to scuttle back and forth, and the little shore crabs (Pachygrapsus crassipes) are always on the move. They are quick to run for cover when approached, but will come out and resume their explorations if you sit still for about a minute. They are really fast and difficult to catch, perhaps not quite as challenging as the Sally Lightfoot crabs that so enraged the crew of the Western Flyer during Ed Ricketts’ and John Steinbeck’s excursion to the Sea of Cortez, but hard enough to be not worth my effort. Fighting is an option only for those equipped to fight. Rock crabs (for example, Romaleon antennarium) remain hidden under algae or partially buried in sand, but when exposed they come out with big claws open and ready to pinch the hell out of anything that comes close. These are the only animals that I really worry could hurt me in the intertidal.

Which leaves the hold-still-and-hope-not-to-be-seen option. This is what decorator crabs do. In terms of temperament, decorator crabs (of which there are several species) are placid and unaggressive: they will pinch when provoked and it can hurt, but they won’t do the kind of damage that a rock crab would happily inflict. Decorator crabs hide in plain sight by covering their carapace and legs with little bits of the environment, usually algae. A well-decorated crab can be sporting several species of algae on its back.

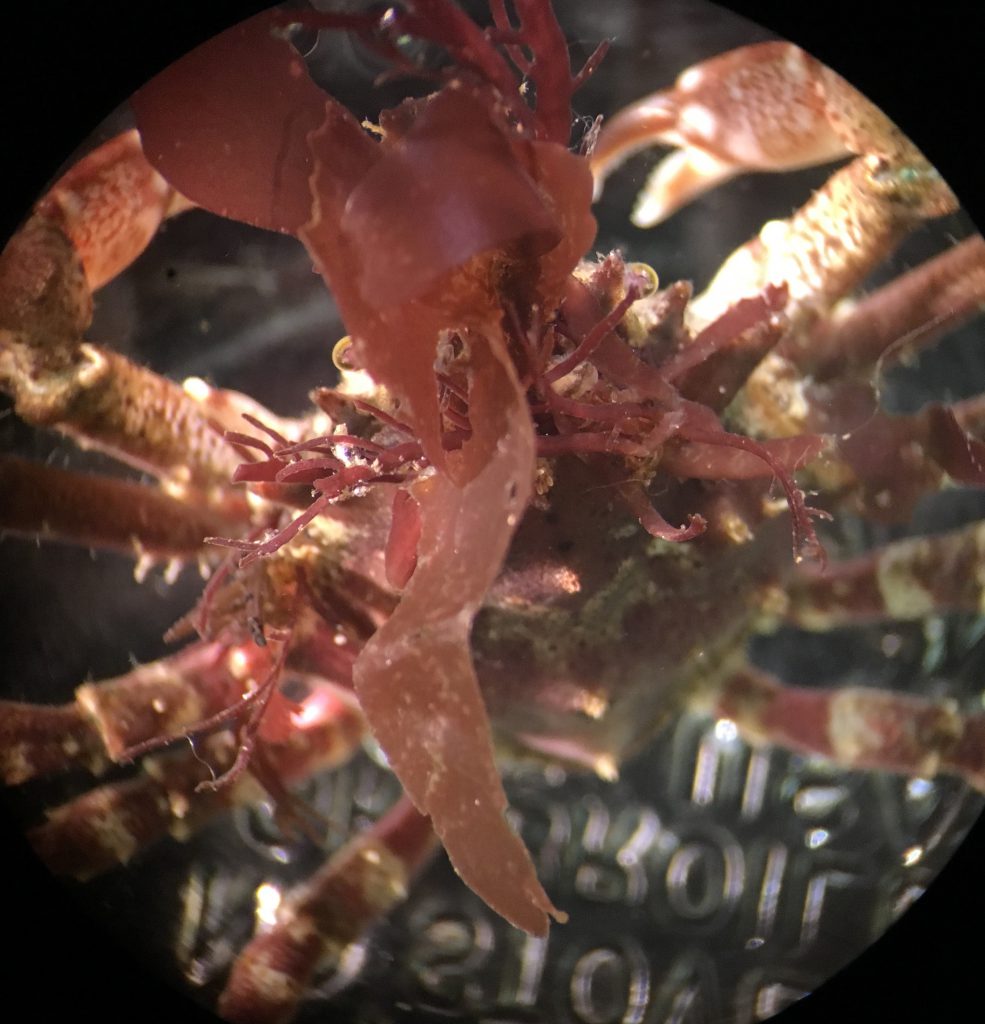

This morning I saw and collected this small crab:

11 July 2017

© Allison J. Gong

I actually didn’t see it at first. I was pawing through the thick algal growth and felt its little feet scratching my hand. I peeked under the algae and there was the crab. Its carapace is about 2.5 cm across, and its claws probably wouldn’t be able to pinch human skin even if the crab tried to. Which it certainly didn’t. I wanted to observe the crab more closely in and keep it for use when I teach the crustacean diversity lab this fall, so I brought it back to be examined under the dissecting scope.

The crab’s own color is a dark brownish red, which helps it hide amongst the red algae. It adds to the environment-as-appearance effect by attaching at least three species of red algae to its carapace. The crab does this by grabbing a piece of algae with one of its claws, then reaching up and behind its head to put it on the carapace, which has has tiny hooks that hang onto the decoration. It’s a very nifty scheme, but there’s one big problem. Each time the crab molts it loses its decoration and has to acquire its accessories all over again.

Example #3 (not obvious at all): Lottia digitalis

We have about a gazillion species of limpets on the California coast. Well, not really but it certainly does feel like it. To make things even more difficult I can’t seem to keep the current scientific names straight. I know that many of the commonly encountered intertidal limpets have been consolidated into the genus Lottia (this includes species that I learned by another name way back when) and I’m slowly getting used to recognizing the Lottia “look”. However, aside from the owl limpet (L. gigantea), which is much bigger and more conspicuous than any others, the other species are difficult to distinguish and I can never remember if species x has the deep ridges or if that’s species y. Ugh.

Earlier this spring I was in the field with my friend Brenna, and she was showing me the differences between Lottia scabra and L. digitalis. Brenna studies molluscs so I know she knows what she’s talking about. Lottia scabra is now easy for me to recognize, but L. digitalis is both trickier and more interesting.

25 June 2017

© Allison J. Gong

See how those all look like limpets? Now look at this:

Do you even see the limpets?

The large animals in the photo are gooseneck barnacles, Pollicipes polymerus. They live on and amongst mussels in the mid-intertidal. This spring Brenna told me that Lottia digitalis comes in a morph that lives on and looks like Pollicipes. I’d never seen it until today. Look at the photo again. Can you see the limpets now?

Here are some more photos.

Isn’t it remarkable how these limpets have exactly the colors and pattern as the plates of Pollicipes? And I didn’t even know about them six months ago. I love having new things to learn and more reasons to pay closer attention to creatures I tend to take for granted. I think it’s time for me to tackle the challenge of identifying limpets in the field. Next season, that is. Today was probably my last day in the intertidal for a few months. We won’t have decent low tides during daylight hours until November.