Tomorrow my students will be examining cnidarian diversity in lab, so early this morning I went to the harbor to collect hydroids. Or ‘droids, as I refer to them. These are not the droids of Star Wars fame, such as C-3PO and R2D2, but rather colonial cnidarians. As such, they are made up of many iterated units (called zooids) connected by a shared gastrovascular cavity (GVC), or gut. Despite how weird it seems to most people, this sort of colonial lifestyle is not uncommon among marine invertebrates; it occurs in several other taxa as well, most notably the Anthozoa (sea amenones, corals, and others), Bryozoa (bryozoans such as Membranipora), and Urochordata (sea squirts).

On my various trips to the harbor over the past few months I’ve been keeping an eye out for ‘droids, as I knew I’d need them. The one species I was glad to see getting established this summer is called Ectopleura crocea; it is one of the non-native members of the fouling community that shows up in harbors all along the California coast. It is a most beautiful animal, and quite conspicuous when it is present. This year I’ve seen it growing lustily on the docks, mussels, and any manmade object that has been marinating in the water for a while.

In situ it looks like this:

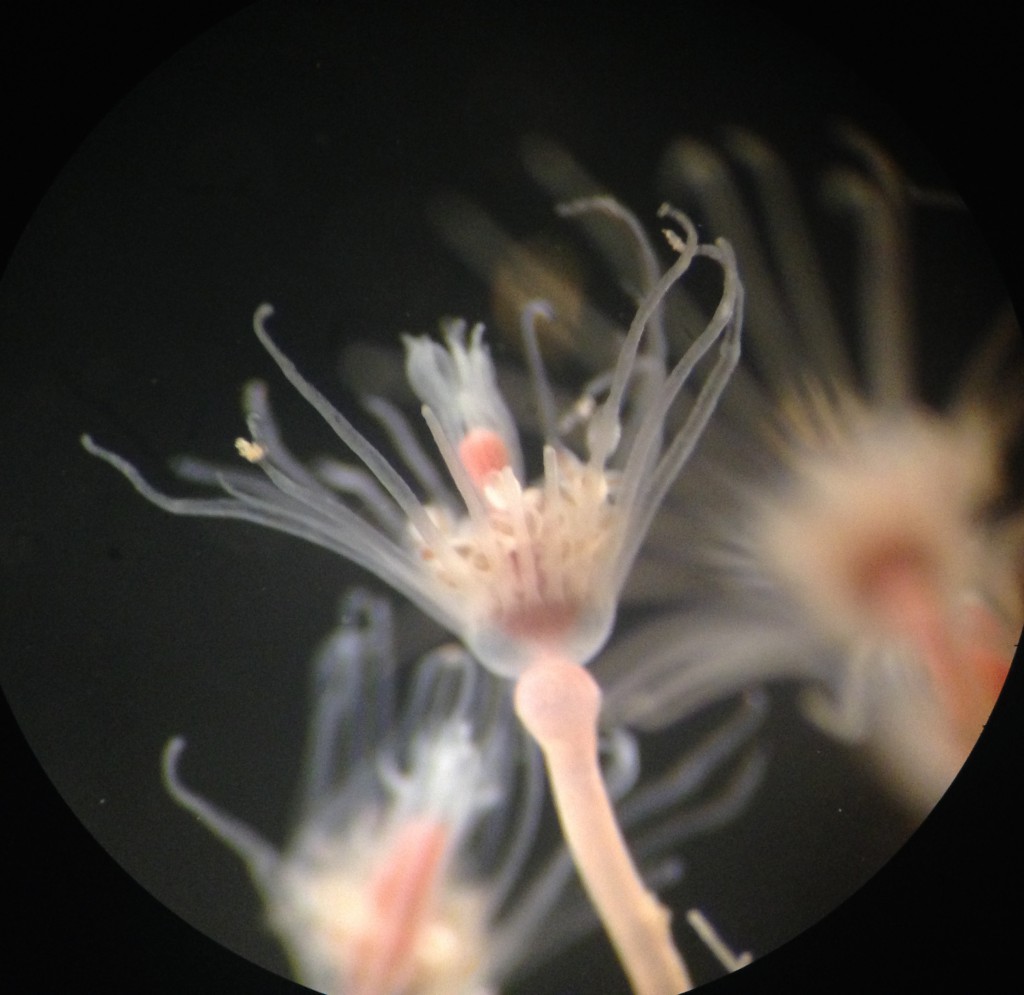

The stalks in this particular colony are 3.5-4 cm long. Each one of those tufts at the end of a stalk is a hydranth, the part of the zooid that bears the feeding tentacles and mouth. Hydroids are cnidarians and thus have stinging cells along their tentacles, which form a ring surrounding the mouth.

Ectopleura hydranths actually have two concentric rings of tentacles, with the mouth in the middle of the smaller ring. Between the tentacle rings there is a sort of empty space that is filled with reproductive structures called gonophores when the colony is preparing for sexual reproduction. In some hydroids gonophores release medusae, but in Ectopleura they release gametes. A given colony is either male or female, and any one of the hydranths can become reproductive and develop gonophores.

Hydroids are definitely animals whose beauty is better appreciated when observed under a microscope:

In the colonies of E. crocea that I’ve observed before, mature male gonophores are a solid white and female gonophores are pinkish. I collected three clumps of Ectopleura today, and none of the gonophores are mature. You can see why the common name for this animal is “pink mouth hydroid,” as the mouth is borne on a pink tubular structure called a hypostome.

I’ve tried multiple times to grow this animal in the lab. There are some experiments on resource sharing in hydroids that I’ve been wanting to do for years but haven’t yet found the right species to work with. In captivity Ectopleura eats well, then after several days all the hydranths drop off and the colonies die. I’ve never had success getting them to regrow their hydranths, either. So I bring them in for short periods and observe them up close while I can.

1 thought on “These ARE the droids I’m looking for”